Finding William - part 2

How I decoded the William Morris grave stones.

A Chance meeting

My discovery of the William Morris gravestones and their hidden message began at a cocktail party in 1978.

The spring semester at Illinois State was winding down and in celebration, the department chair hosted a gathering of the 15 or so graduating archaeology students.1 The special guest present, James Deetz, was prominent in historic archaeology and is regarded as a pioneer in academic gravestone analysis.2 Inspired by Deetz, I realized that gravestones could be seen as artifacts to be studied, not merely art history curiosities. Importantly, artifacts were a way to enter the mind or “mental template” of the maker of those artifacts. This thought would lay dormant for the next 41 years.

In 2019 with the discovery of the identity of the carver of those crudely beautiful grave markers at Union Cemetery, I set about to document and analyze them. Although I would later draw on expertise from the Association for Gravestone Studies,3 the initial effort was sui generis. Let’s just look and see what we find.

Photograph

I quickly learned that a high quality photo under magnification was much preferred to naked eyes from a hands and knees prone position in bad weather. But before they can be photographed, cleaning was needed.4 See endnotes for a discussion on cleaning. For a primer on graveyard photography click here:

Five Easy Steps for Better Grave Stone Photography

At six months into the project, the details became overwhelming. The fonts were crazy, misspelled words were rife, lines off center, and ordinal indicators were missing. Morris would slip in one italic letter into a word otherwise inscribed in Roman font. I had to organize this chaos.

Document

To bring a systematic approach, I created a two page form that would capture the data I thought might be relevant. Through trial and error, the form was updated and emerged as follows:

A significant breakthrough was made using a formula to convert size to weight. The formula was updated several times but ultimately settled on H.A.G. (height above ground) plus ten inches X width X thickness divided by 1,728 cubic inches X 145 lbs.5 This would derive an estimated weight in pounds. We tested the formula in several examples with markers that could be weighed. A sheet of heavy plywood and a bathroom scale created a workable field method to compare actual weight against estimated weight.

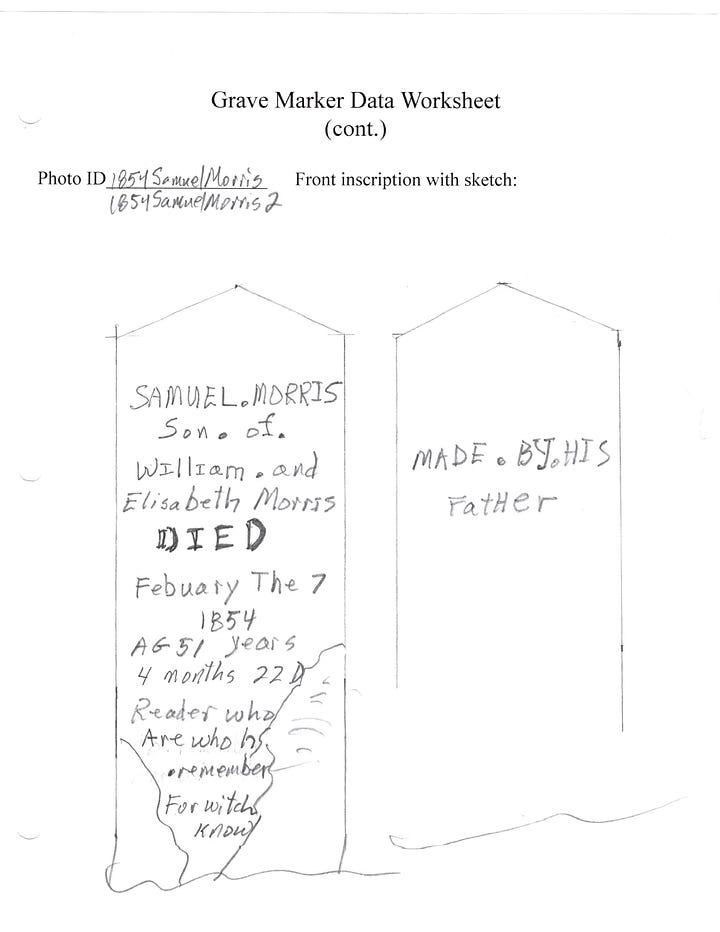

Data was collected on dimension, font style, date of death, age at death, inscription, genealogical relationship to Wm. Morris, and idiosyncrasies diagnostic of the carver. An intensive period of study stretching over six months was spent inspecting every single letter and numeral on each of the 27 extant grave stones. There was also attention given to the pediment style (design or angle of top) and the three epitaphs that were found.

Inside the mind of William Morris

The genealogical relationships represented in the William Morris gravestone are typical for an amateur carver. Twenty-six were placed over the burials of close and extended family. Only three were non familial; one man presumed to be a close friend as well as two infants belonging to a neighbor.

William’s carving style changed with time. Grave stones carved before 1837 had a flat top three and after that year exhibit a rounded shape. This appears to have been a pragmatic change as the rounded three seems easier to carve. Two semilunar cuts and two drill holes made an elegant numeral three. The flat top 3 is found on the stone carved for his wife Betsy who died in 1831 and may have been copied initially from that source whereas the rounded three is typical of local carvers. William appears to have copied what he saw locally and found it preferable.

Morris did not know how to use ordinal indicators.6 Here we see in the photo below the use of 3th instead of the correct 3rd. More often Morris would simply ignore it choosing to just write the month and day with no use of ordinal indicators.

Spelling errors, inconsistent font, and other details give the impression of a carver with only a rudimentary education. We know from genealogical records that William came with his family from England to S. Carolina at age 12. Was that when his education was halted?

Age played a role. William Morris carved grave stones between 57 and 83 years of age. Words like “an” and “and” are confused while others are repeated. The effects of diminishing physical and mental abilities are readily apparent in his later work. Even though he lived to age 97, he seems to have given up stone carving at age 83 in 1860.

Another interesting shift in Morris’s work is the change from a stylized soul effigy7 to a Neo-classical pediment. This shift occurred in 1853 after which year, he no longer used the prior shape, choosing instead a peaked pediment approximating the roof angle in Neoclassical architecture.

What caused this shift?

Was the concurrent building of the Washington monument the inspiration? Or perhaps the change was somehow driven by the sheer volume of cholera deaths during the 1852 - 1854 period?

Something else happened in 1853. The 1852 death of Mary Anderson Shannon was memorialized with the first marble obelisk at Union Cemetery. The lag time between death and the erection of a monument can vary but about a year is typical. Did William Morris copy this new trend in monuments with his own “homemade” obelisk?

It’s clear that the twenty years between 1834 and 1854 brought staggering change to southwestern Illinois. Frontier days ended by 1840 as population growth and technological development reworked the landscape. The many small adjustments in William Morris’s stone work reflect this transformation. But there was one constant throughout his life that did not change — the weighing of a life.

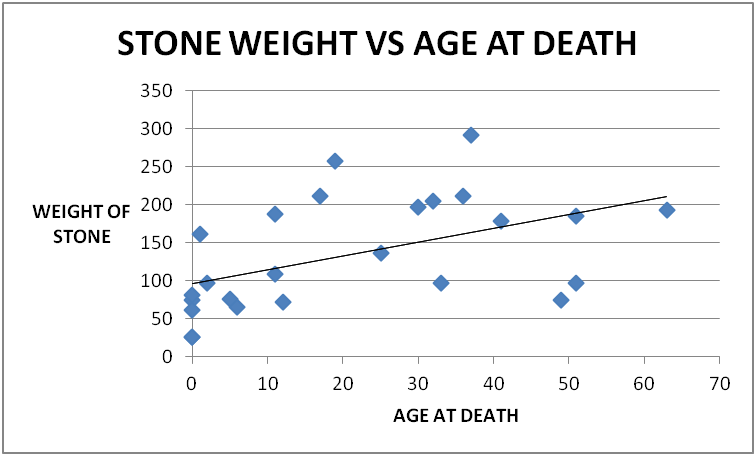

I first created a spreadsheet tabulated with date of death, age, and estimated weight of stone. This gave us the following expected result; mostly random with a slight correlation between age and weight. Children get smaller markers than adults.

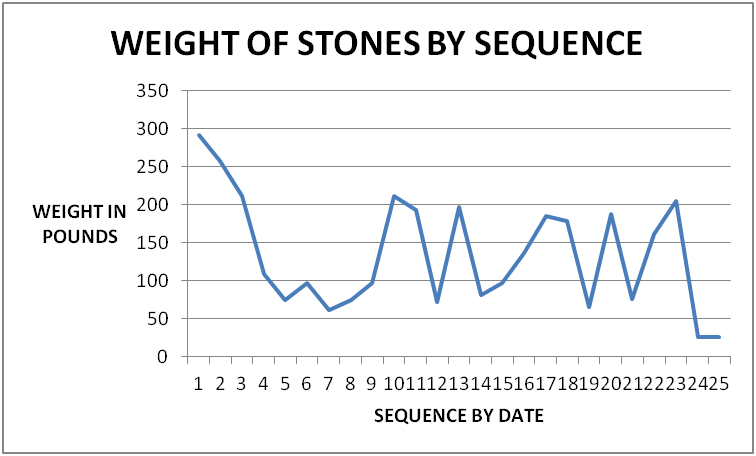

Next, I thought perhaps that there was a change in weight over time simply due to Morris’s declining physical ability. Except for the last couple of stones in 1860, the data did not support my theory.

Morris seemed to be making two sizes of markers. One about 80 lbs. while the other clustered at 200 lbs. The monument for his wife Betsy was much larger and made by a professional carver weighing an estimated 300 lbs. The last three he made were very small, only weighing about 30 lbs.

Then I remembered a technique in statistics when working with limited data sets: data smoothing.

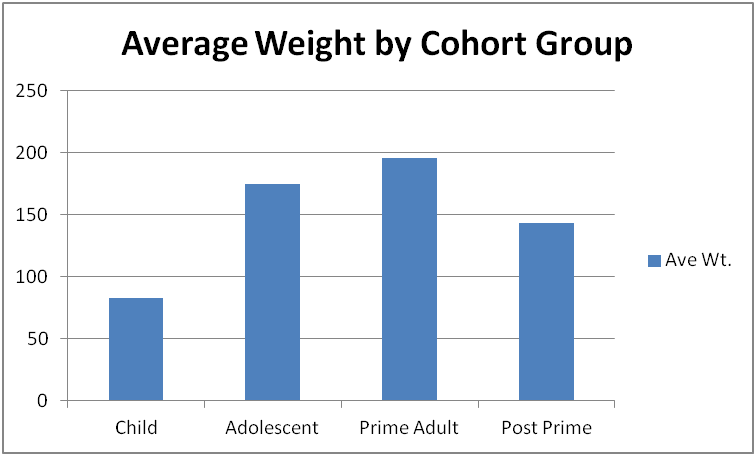

It is well known in grave marker studies that children tend to get smaller gravestones and adults larger. But I did not expect to find so finely tuned a weighing of a life. Eerily reminiscent of Antebellum slave auction prices, I thought it might signify the economic worth of the deceased whereby young adults are valued more than either children or aged individuals.8

But the Morris collection was different. If anything, females in their prime received a larger monument than males. What was going on here? Was the size of grave markers an unconscious reflection of grief felt by William Morris? Consider the difference in funeral attendance between a 90 year old who has outlived all their friends versus the tragic death of a young adult from a sudden accident.

Is the Morris data documenting economic loss to the community or the personal grief felt by Morris?

Now imagine the loss of 37 year old Betsy Morris with ten children between the ages of 17 years and 6 months. This tragic death seemed to be the tipping point when William Morris channeled his grief into the carving of grave stones.

It is possible his grandfather back in England was involved with stone carving. It is also likely Morris chose his Illinois property full well knowing it had a good source of sandstone for carving. But it was the death of his beloved Betsy, that energized him to memorialize the members of his family in stone.

To see all of William’s grave markers click on the link below:

Gravestones carved by William Henry Morris

An undergraduate degree in Anthropology with specialization in archaeology. Many students then also had a minor or double major in History.

James Deetz, In Small Things Forgotten: An Archaeology of Early American Life, expanded and revised ed. (New York: Anchor Books/Doubleday, 1996).

The Association for Gravestone Studies (AGS) was founded in 1977 for the purpose of furthering the study and preservation of gravestones.

Do not use bleach, vinegar, ammonia, dish soap, metal tools or any abrasive. If you don’t understand the science of cleaning historic gravestones, it’s best not to use anything except water and a soft natural bristle brush. I know of no cleaners you can commonly buy that would be safe to use. Knowledgeable people follow recommendations by the National Park Service which is generally limited to QUAT’s or Quaternary Ammonium Compounds for removing biologic deposits. Orvus, a common quilt cleaner is sometimes used for removing heavy clay deposits. Bleach is the most despised cleaner because once used, the process is irreversible, slowly dissolving the stone.

The formula uses measurements to arrive at cubic inches then converted to cubic feet and multiplied times 145 which is the weight in pounds of a cubic foot of sandstone. A constant of ten inches is added to the height above ground as that is the approximate average of the below ground portion of the grave marker.

Ordinal indicators are abbreviated letters used in conjunction with numerals to indicate order as in 1st, 2nd 3rd.

A stylized soul effigy is derived from Puritan era seventeenth century winged skulls that adorned the tops of gravestones. Later the motif evolved into the classic winged cherub. And here with William Morris the motif evolution is complete as represented in abstract geometric shapes.

Fogel, Robert William, and Stanley L. Engerman. 1974. Time on the Cross: The Economics of American Negro Slavery. Boston: Little, Brown, 76.