FINDING WILLIAM - part 1

William Morris, amateur Illinois grave stone carver known by name and biography.*

I was eight or nine rummaging my grandmother’s built-in pine drawer for photographs when my hands found their way onto a small red book, Records of the Morris Family.1 It was one of those vanity genealogy books popular in the early twentieth century. The date was missing but seemed 1920s era.

The Records of the Morris Family

The book claimed that Sam Morris (William’s grandfather, 1712-1798) was a member of the town committee in Stratford, England that restored the Shakespeare Funerary Monument in 1748. The town effort was quite a production and included the John Ward theatre company performing Othello in 1746 as part of the fund raising effort.2

Samuel Morris, Sr., was on the Committee which restored the tomb of Shakespeare in 1748, containing the famous curse upon any who should disturb his bones. 3

The Morris book exhibits a family song, family crest, and a desperately vain attempt to connect to European royalty, typical genealogy of that time. Evidence is presented that the Morris and Shakespeare families were intertwined in a variety of ways. William Shakespeare as a baby may even have nursed from the breast of a Morris woman. Without her, would there even be a Shakespeare?

Kathryn Morris served in the Shakespeare home in some capacity during the boyhood of the poet, as that fact is made a matter of record at the time of her death in 1587. Whether she was his “governess,” “nurse,” or “maid” cannot be determined. - S. L. Morris

In 2006 I attended a business conference in London. We arrived at Heathrow two days after the failed August 10th terrorist plot. The airport was still locked down with no departing flights. Only incoming aircraft were permitted. Special ops forces clutched their automatic rifles in silence. Grim expressions adorned the faces of serious men who were expecting to kill someone and possibly might enjoy the task. As if to punctuate the gravity of our arrival, by chance, our hotel room overlooked the police station where the Pakistani terrorists were locked up. The media was buzzing, the circus had come to town.

With a day to myself, eager to leave London and the land of sidewalk hookahs, I took the train out of London to Stratford on Avon. Arriving in Stratford, I made my way to the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust and asked to see the head librarian.

“I am a descendant of the Morris family here in Stratford. What can you tell me about them?”

“What took you so long? Follow me.”

Considering the last family member to contact the Shakespeare archives was about 85 years previous, it was a deserved response. I stood there like a schoolboy a week late with his English composition.

I followed behind, barely keeping up as she pulled books, photos, and manuscripts off the stacks to place in my open arms. At last she turned, “That’s about it then. You can read in there and no photos, no ink pens. Only pencil.” I never saw her again and I don’t remember the name.4

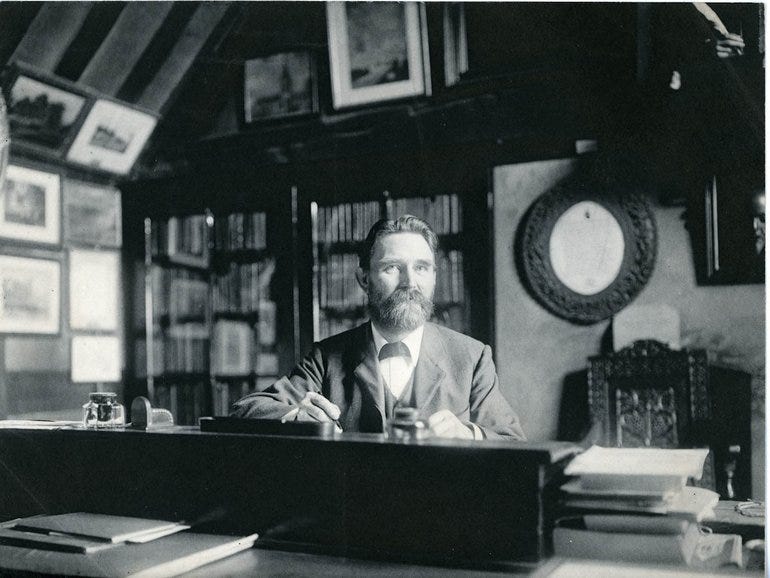

I later found that the research for The Records of the Morris Family had been conducted by none other than Richard Savage, an early librarian of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. Savage made a great impact on SBT (1884-1910) enlarging the collection, updating transcriptions of original documents and organizing the properties included in the SBT. Importantly, he moonlighted as a genealogist for hire.

Having now ascertained the ancestral home of our family in England, I began a correspondence immediately which led me to employ Richard Savage, of Stratford, England, an expert genealogist, to search the parish records for our family history. - S. L. Morris

I was humbled that a third cousin twice removed had employed the head Librarian at the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust to research the family history. Even more wondrous, a succession of head librarians had been waiting for some member of the Morris family to contact them again. And 85 years later, on a whim I had barged in unannounced. I was the one.

On the way back to London, the train broke down and passengers were directed to walk the tracks to a nearby car park and waiting bus. I was reminded of the old adage that Germans are better engineers, and French better cooks and so on. But at that moment I was grateful the English know how to run a library!

CARVED BY HIS FATHER

Thirteen years later — I retired in July 2019 but by April of that same year had already begun to spend more time on genealogy and cemetery rambles. About the same time, I made contact with a fourth cousin on the Morris side through a DNA connection via Wiki-Tree. Our research meshed, she from Germany5 and me in southern Illinois. An occasional email kept us both on task.

And that led to the mystery of Samuel Morris, the oldest son of William Morris by his first wife. The entire Samuel Morris line died out leaving more questions than facts. Even the location of Samuel’s burial place was vague. It was this minor mystery that would completely upend our research.

—Samuel, born Sept. 15, 1802,) was son of William Morris, Sr., by his first wife, and died age 54 close to Grand Tower, Illinois, and is buried across the river on the Bluffs just north of Wittenberg, Missouri. He had a daughter who married Swann. All of his family are dead.

- S. L. Morris

Many years earlier, I explored the bluff area north of Wittenberg and found a small destroyed cemetery completely rooted by hogs. Disappointed, I wrote it off as lost. In 2019, I went back to the area this time to Brazeau. Brazeau, Missouri is an unincorporated area five miles west of Wittenborn, not North.6 It had a Presbyterian church, and the Morris’s were Presbyterian. The odds were slim but I had to look. Imagine my delight finding the Brazeau cemetery in great shape and not only did I find the marker for Samuel Morris, but two of his sons as well, James and William.

The grave markers are carved from a peculiar sandstone7 that I had noticed before in Union Cemetery, forty miles distant. The stone was from the same source but how and why?

The breakthrough came by accident on November 4, 2019.

The sun was setting, turning colder. I turned to go, satisfied with finding the Samuel Morris grave marker. My foot slipped just then causing me to wrench my body around spinning to keep my balance and in so doing found myself looking at the back of Samuel’s marker. And there it was, “MADE BY HIS FATHER.”

In a lightning jolt moment, I now knew the stone carvers name. Written in stone — it was William Henry Morris!

The Life of William Henry Morris

William Henry Morris was born June 7, 1777, christened at St. Helen’s Church in the small hamlet of Clifford Chambers, England, just four miles distant from Stratford-upon-Avon. Morris immigrated with his siblings and parents to the Abbeville, South Carolina area in 1789. In 1802 he had a son with his first wife who died soon after. He and his son, Samuel, later moved to Preble County, Ohio, shortly after 1810 where he bought land and married his second wife Elizabeth (Betsy) Newton, seventeen years his junior. Military records from the War of 1812 indicate that Morris was a private in Captain William Ramsey’s Ohio militia company during the winter of 1813-1814. By the summer of 1816, William and Betsy had two young children and another coming in October, but late that year followed the decision already made by many and joined the stream of emigrants moving once again; this time westward to Illinois Territory.8

In the 1894 Randolph County atlas, son Isaac recounts the life of William Morris:

He came to Illinois in 1816, locating upon the old Morris homestead. He entered from the government a farm of one hundred and sixty acres, built a log cabin and began life in true pioneer style. In politics he was a Republican and was a member of the Masonic fraternity. He also belonged to the United Presbyterian Church. He was a very temperate man, never using tobacco or intoxicants, and he left to his family the priceless heritage of an untarnished name.9

From their arrival in 1816 until 1831, I found no recorded deaths in the Morris family.

On June 6, 1830, Betsy Newton Morris bore her and William’s last child; a daughter named Alice. Six months later, Betsy died on January 15 in the deepest part of the winter of 1830-1831, an exceptionally harsh winter much written about.10 11

Perhaps reflecting Morris’s great loss, Betsy’s marker is large, elaborate, and obviously made by a professional stone carver. In addition, there are two heavy rectangular stones laid on top of her grave that create the effect of a ledger stone. Her grave is oriented on an East West axis, facing east, but the inscription is on the west side of the marker.12 William Morris was then fifty-four years old.

The first two markers actually carved by Morris were for his two children Jane and Newton, aged twenty and nineteen who died of cholera on the same day, July 18, 1834.13

Counting just the known examples, Morris would carve markers for at least twenty-seven more burials of family and friends over the next twenty-six years. The twenty-nine markers are spread among three cemeteries in Randolph County, as well as the Brazeau Presbyterian Cemetery in Perry County, Missouri, forty miles distant. New Palestine Cemetery is Methodist affiliated and contains only one distant in-law relationship. The other twenty-eight burials are in Presbyterian Church cemeteries, Old Bethel, Union, and Brazeau.

Morris may have been motivated by emotion or family duty but it was certainly not money. A search of probate records revealed no evidence that William received payment for any of the markers he carved.

What events impacted Morris’s urge to create these grave stones?

We know his Stratford school boy education was halted by immigration to South Carolina at age twelve. And there is evidence to demonstrate that the Presbyterian Church was important in his life.14He was also no stranger to death, having lost his mother at age thirteen and his first wife in his mid-twenties. The death of his second wife Betsy at age 37 in 1831 must have also been a terrible blow. It was after her death that he seemed to take up an interest in grave stones.

One additional factor that differs from other known stone carvers is Morris’s age. He carved grave stones from age fifty-seven in 1834 until at least age eighty-three in 1860. This alone accounts for some characteristics of his work.

Morris’s English education, Presbyterian faith, advanced age, and intimate experience with death form the core experiences that affected his stone carving.

Archaeologists believe that artifacts are the embodiment of ideas. So, if we study a set of artifacts in enough detail we should theoretically be able to enter the mind of the creator of those artifacts. It was that guiding principle that set me on a mission to enter the mind of William Morris. And what I found was amazing.

Read part 2. of this two-part series to find the hidden messages of gravestone carver William Morris.

Part 2: Hidden messages in the William Morris grave markers revealed.

* Hal Hassen and Dawn Cobb in their book Cemeteries of Illinois, U. of I. Press, Urbana, 2017. p. 124, write “We are not aware of any published studies documenting the early work of Illinois grave-marker carvers or assessing folk art on grave markers in Illinois.”

S. L. Morris, Records of the Morris Family (Atlanta, GA: Hubbard Bros., 1922).

I could find only two names associated with the 1748 repair of the Shakespeare funerary monument, Rev. Joseph Greene and limner (painter) John Hall. Given the references to community involvement, it is likely many townspeople were involved in lessor roles. Richard Savage may also have had access to obscure documents that even today are not available via the internet or A.I.

S. L. Morris, Records of the Morris Family (Atlanta, GA: Hubbard Bros., 1922) Citing Richard Savage, librarian Shakespeare Birthplace Trust 1884-1910.

I later learned the woman’s name was Sylvia Morris, prominent Shakespeare researcher and former librarian at the Shakespeare Center and Library Archive. I do not know if she is a related Morris but it explains her familiarity with the Morris family.

Fourth cousin Carole Morris Pancake is an American who temporarily lived in Germany for work related reasons. She is a librarian and genealogist of high caliber.

This mistake was likely due to the assumption that up-river and north were synonymous. At this stretch of the Mississippi River, it flows east which means the cemetery location would be west, not north of Wittenborn, Missouri.

The sandstone is identified as Palestine Sandstone and the exact source is thought to be from the creek bed of the Little Mary’s River that runs through the Morris property in T. 5 S. R. 6 W. Sect. 26 SW 1/4, Randolph County, Illinois.

Land records at the Bureau of Land Management reflect that Morris assigned ownership of his 160 acres of land in Preble Co. Ohio to another person November 1816. The decision to move to Illinois was influenced by the widespread crop failure that year attributed to the abnormally cold and dry conditions caused by the Mt. Tambora volcanic eruption of 1815.

Portrait and Biographical Record of Randolph, Jackson, Perry and Monroe Counties, Illinois, (Chicago: Biographical Publishing Co., 1894) 293-294.

James E. Davis, Frontier Illinois (Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1998) 244.

Shaw, David. 2025. “Cause of Death: Finding the Cause of Death in 1800s Randolph County, Illinois,” Serengenity, (Substack, September 3, 2024), https://serengenity.substack.com/p/cause-of-death.

Standing there reading the inscription a visitor would not be standing on her grave as was the older custom of English burials.

Shaw, David. 2025. “One Grave, Two Lives: Cholera Tragedy of the Morris Family.” Serengenity, September 30, 2025. https://serengenity.com/one-grave-two-lives-cholera-tragedy-morris-family.

H. Leonard Porter III, Destiny of the Scotch-Irish, an account of a Presbyterian migration 1720-1853 (Knoxville, Illinois: The Porter Company, Inc., 1985) 30.

How sad that he had to carve hs own son's headstone. How serendipitious you twisted to see the back side of the stone. Looking forward to part 2.

Great work! Looking forward to part II.