I have X-Ray vision.

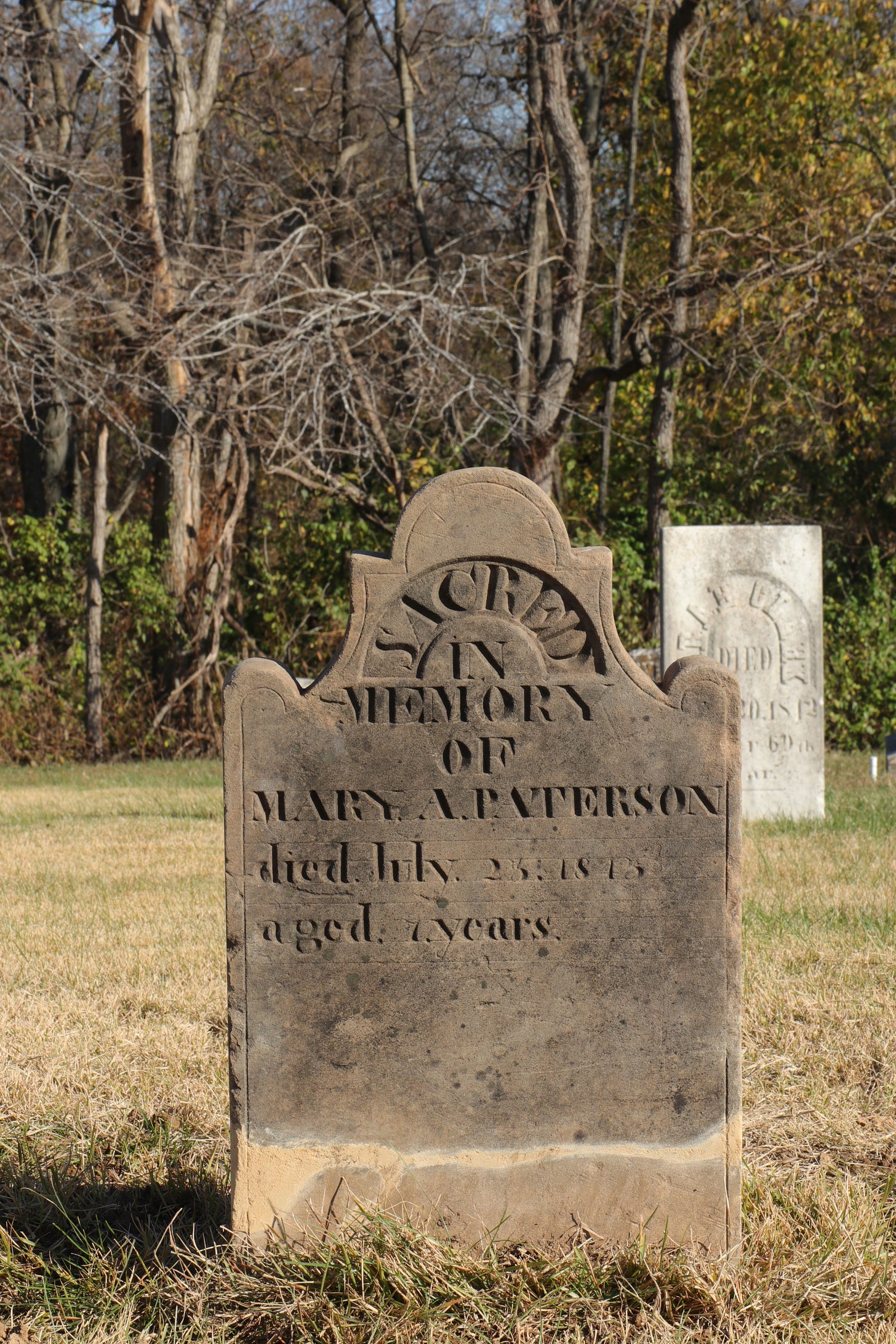

Not literally of course, 1960s era comic book ads notwithstanding. I just tend to think spatially. Turns out it is a handy skill in researching and maintaining historic cemeteries. The grave marker that you see above ground is only half. The rest is, well, buried. Come along as I show you what we found at Union Cemetery in Randolph County, Illinois.

The Unfinished Bottom

The underground portion of many of the earlier sandstone markers are simply “unfinished.” It was a format adopted by many of the stone carvers of this period in 1830s-1840s. It was hard work carving sandstone with chisel and mallet so it makes sense that a carver would not waste energy on work perceived as unnecessary. In many cases, the unfinished “blob” at the bottom of the marker added extra weight helping it to stand like toy Weeble Wobbles. Here is an 1843 marker on the repair bench showing the extra weighted bottom. This style is prone to leaning but many have held up well, just needing a bit of re-positioning. This one likely got hit by a lawn tractor during the 1960s before the invention of the zero-turn mower.

Slotted Stone Base

With the importation of finished marble blanks, a new problem was created for the local stone cutter. The desirable (and high cost) imported marble was appearing in Southern Illinois by at least 1830 but was not in high volume until after 1848 when the “lustrous stone”1 replaced sandstone and siltstone almost entirely. From 1830 to 1849 we see the various stone types coexisting during this transitional period.

The installation of a marble marker into the ground in an upright position required a different solution, however. This marker from 1849 at the end of the sandstone era shows the rectangular marble marker set into a base made of local sandstone. The base has a receiver slot just large enough to accommodate the rectangular marble marker. This is referred to as mortice and tenon or slotted base method of positioning the marker upright. The marker shown below is the only known example at Union Cemetery using molten lead to seal the marker into the receiver slot. The majority used mortar or other concoctions to seal out moisture.

Full Slot Base

This style of base is my favorite for two reasons: it was the type made by my Gr Gr Gr Grandfather, William Henry Morris, and it ingeniously solves a key problem of gravestone installation.

Gravestone mechanics revolve around two key problems: weight and frost heave. For the monument to be stable, the base or footing must be sufficiently large and deep into the soil to avoid movement from frost heave.2 But stone is heavy, so the more resistant to frost heave, the heavier the base and total assemblage.

Morris solved this dilemma in the following manner. The base stone was composed of a three to four-inch-thick piece with the slot cut completely through giving the appearance of a collar. The tolerance or gap between the marker and its slotted stone base was extremely small, running from 1/16 to 1/8 inch on each side. By making such a tight fit, there was no need for additional mortar to fix the marker into place and therefore it “floats” loose in its collar. The marker extends down through the collar to a depth in the soil just below the frost line. The natural fit of the base and its depth placement into the soil was easily sufficient to hold the markers upright. It is difficult not to admire the clever technological solution to the problem of securing the stone below the frost line while minimizing weight.

Mistakes, Fraud and Poor Judgement

One issue we found over and over was improper original installation. I am prone to impute malintent where money is involved but in truth, incompetence and bad judgement may explain just as well. Here is the original found condition of the impressive marble monument for Major James Farnan, M.D. who died in 1877.

Major Farnan was by all accounts, a competent officer in the Union Army but was not universally liked. He received his commission partly due to the fact that his uncle was a personal friend of Abraham Lincoln. The exploits of his unit the “Randolph Rangers” can be found in the book, The Prairie Boys go to War, by Rhonda Kohl.3 Major Farnan’s family history is fascinating, included gifted musicians and the inventor of the step ladder. Dr. Farnan led a colorful life and remains one of our favorite residents of Union Cemetery.

To read more see this link:

Ciregna, Elise Madeleine. The Lustrous Stone: White Marble in America, 1780-1860. PhD diss., University of Delaware, 2015.

Union Cemetery in southern Illinois is roughly the same latitude as Lexington, Kentucky. The ground freezes only to a depth of about 4 inches in even the most severe winter. The Morris collar system of holding markers would perhaps not work as well further north.

Kohl, Rhonda M. The Prairie Boys Go to War: The Fifth Illinois Cavalry, 1861-1865. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2013.

You're just amazing. I love these posts.

I had no idea what was going on underground with these stones. You’ve done fabulous work to bring them back and explain the craftsmanship. I especially like the font choices on that Union soldier one. The restoration really shows off the design.