The dead speak in stone

The surprising history and meanings of epitaphs at Union Cemetery, Randolph Co., Illinois

I hear dead people.

Not literally of course. But gradually I came to understand the sources and hidden meanings of epitaphs found at Union Cemetery. Then one day, like learning a foreign language, I had acquired the language of Epitaph.

/ĕp′ĭ-tăf″/ noun A phrase, image or words inscribed on a monument or grave marker intending to commemorate, dignify, celebrate or otherwise mark the passing of the deceased.

Reading the Stone

Reading stone is harder in practice than in theory due to the worn, lichen encrusted conditions encountered. In order to read epitaphs, we have dug, lifted, cleaned, repaired, reset and meticulously documented many hundreds of grave markers at Union Cemetery. Time, gravity, and natural forces have all taken their toll.

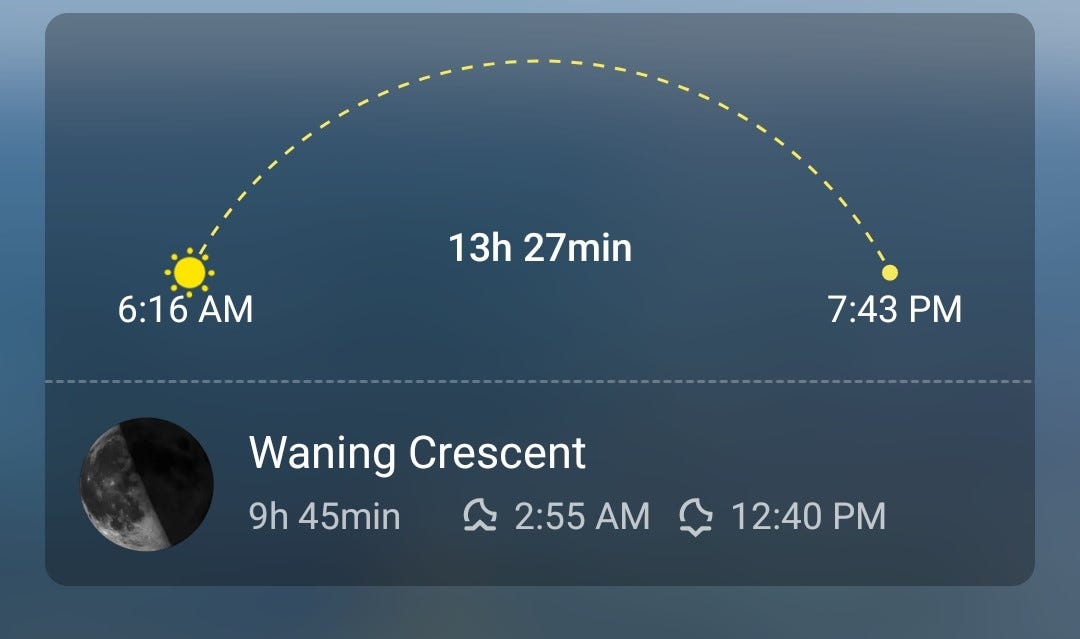

I like reading grave stones on a bright day at the optimum time for oblique light. East facing is best prior to solar noon, West facing after solar noon. A difference of thirty minutes can hide or reveal the words. For shaded stone a similar effect can be created using a high Lumen1 flashlight at varying angles. It’s a bit like working a Crossword puzzle while lying on the ground looking up at a worn piece of stone. Now, what’s a four letter word that begins with “W” and rhymes with sleep?

Solar noon is calculated by finding the number of hours and minutes from dawn to dusk, dividing by two and adding back onto the dawn time. In the example below 13h 27 min divided by 2 is 6h 44min. Added to dawn at 6:16 solar noon would be exactly 1 PM. East facing gravestones would be optimum from about 12:15 -12:45 PM and west facing ideal at 1:15-1:45.

There are relatively few unique epitaphs, thankfully. Most come out of an epitaph booklet used by the local stone cutter or monument dealer. But the original source often traces back to the bible, English literature or popular hymns.

Regardless of source, epitaphs are often repeated on multiple stones with aphoristic variation. That is, you will find the same bible verse or quote, but the exact words vary while still containing the core meaning. Nevertheless, epitaphs fall into several broad categories reflecting their origin, cultural context and specifics related to the deceased.

An Accounting

In lieu of or in addition to a birth date, we sometimes see an accounting of age as expressed in years, months and days lived. This tradition is quite common at most cemeteries throughout the nineteenth century but disappears around 1920 with the arrival of government record keeping.2

While the practice of an “accounting of age” is a secular Anglo-American record keeping custom, it is also part of a larger Protestant Christian tradition. The calculation of age down to months and days underscores the idea that every moment of life is significant in the eyes of God. No bible verse directly addresses an accounting of days lived, but there are plenty of general references such as Psalm 90:10, The days of our years are threescore years and ten.

We occasionally find the accounting to be incorrect due to miscalculation. It is also typical for both the day of birth and the day of death to be included so it often means the accounting will add an extra day compared to how we would normally count elapsed days.

Genealogy & Geography

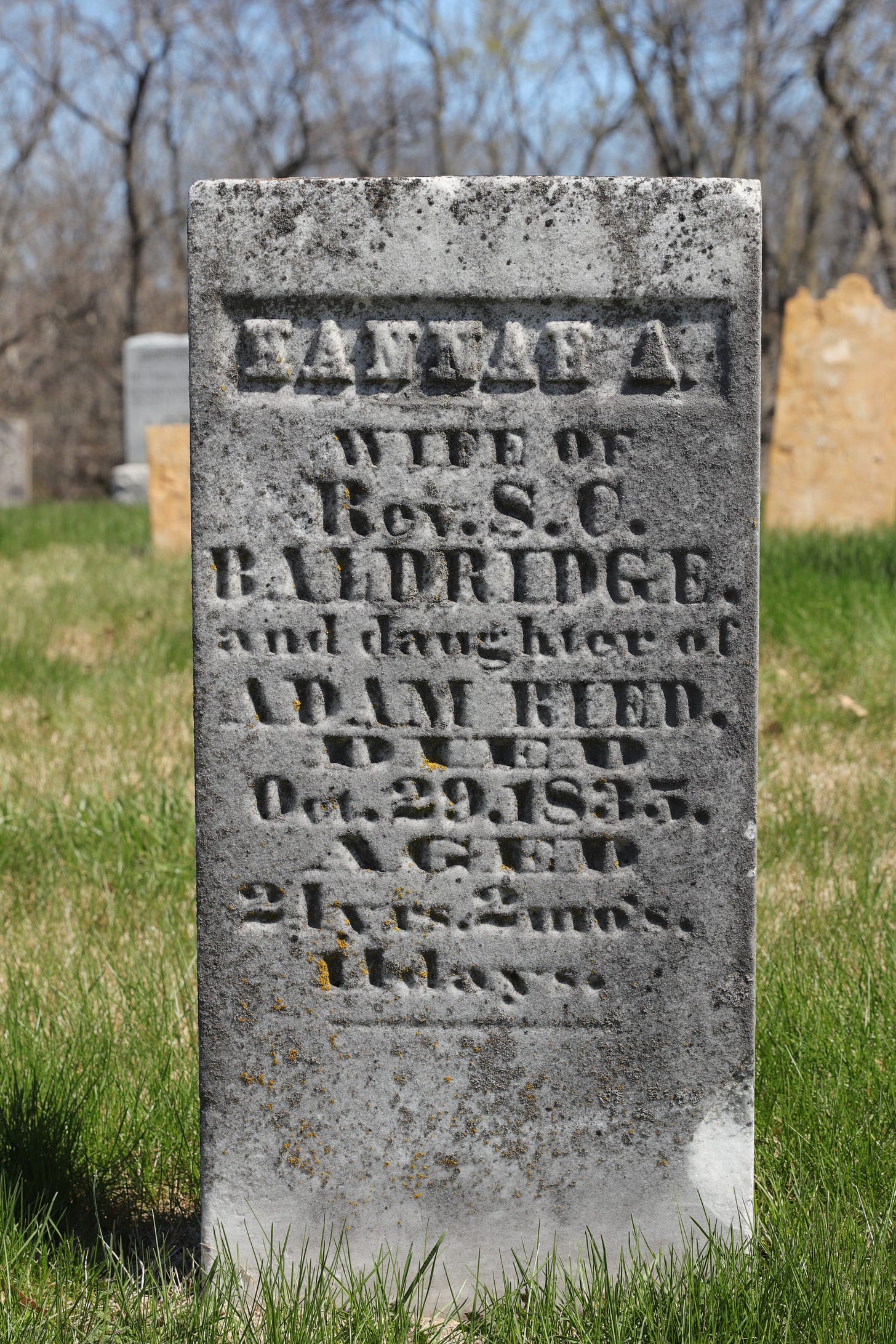

A common complaint by some feminists is that women of past generations seemed to be defined by their relationship to a man, be it husband or father, through the system of coverture.3 In the case of Hannah Baldridge, above, she seems to have made bonus, being defined in relationship to both her father and husband.

There may be more to this than “the patriarchy.” It is good to remember that during the nineteenth century many could not afford a stone marker, so the notation of husband or father may be more an additional mark of social standing, applied to an already expensive monument. Then as now, people also valued genealogy, so before secular record keeping, listing family on a gravestone was desirable if you could afford the extra cost. It is also common to find children recorded in relation to their parents.

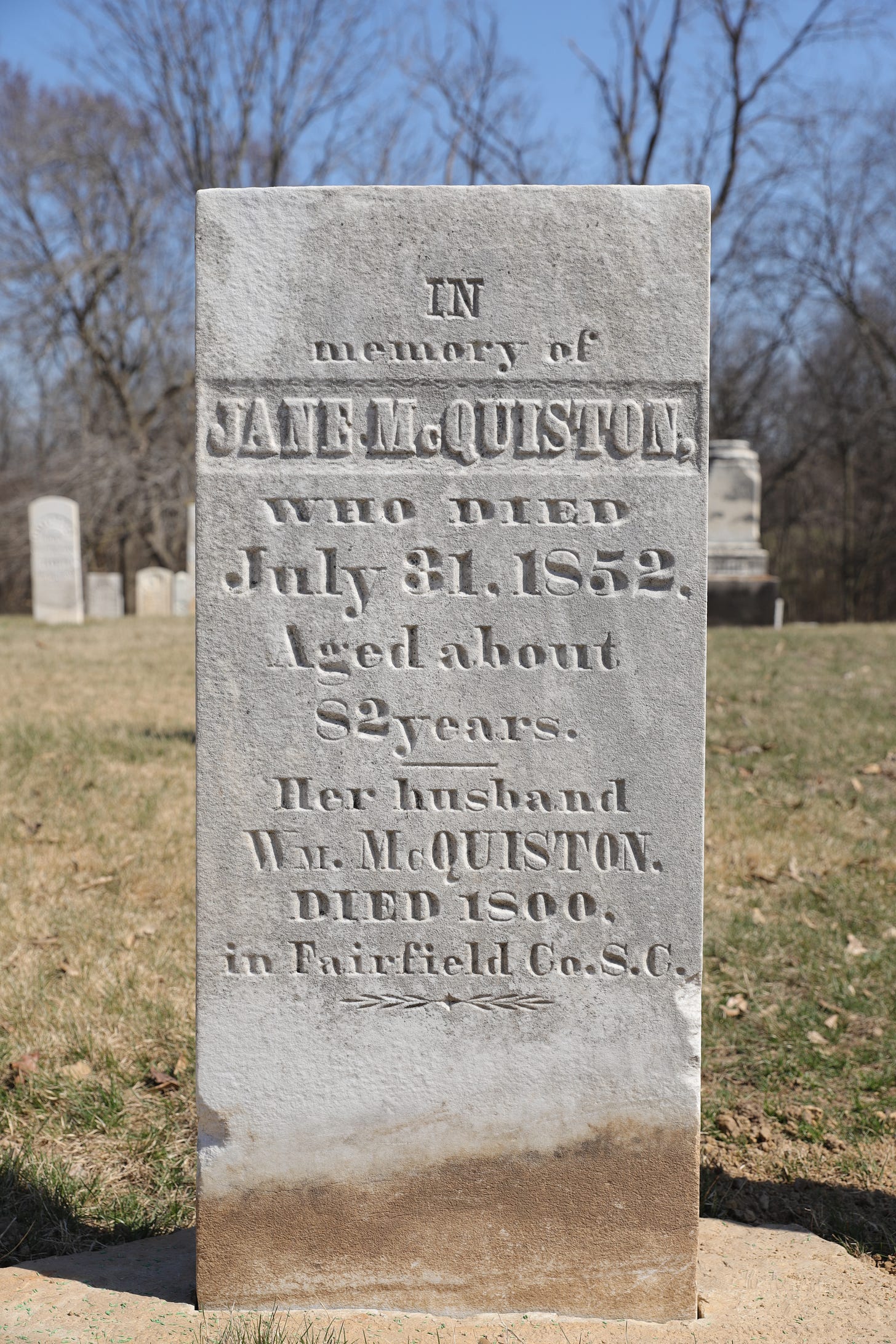

An additional element sometimes found on nineteenth century grave stones is geography. The early pioneers held a deep appreciation, as we do, for their own origin story. The predominant early cultural group in Randolph County was “Carolina Irish,” typically Presbyterian Scots-Irish that immigrated from Ulster to South Carolina and then spread westward to Ohio, Kentucky, Tennessee and Illinois. A significant number in later generations moved on to Kansas. This strong sense of place held by the Scots-Irish is found engraved on their stone markers revealing their ancien domicile4 in Ayrshire, Scotland, Ulster Ireland, Abbeville, South Carolina and Preble County, Ohio. Two other areas tied to the Scots-Irish migration are Washington County, New York and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

As a life long genealogy fan, I am grateful when I find such detailed family knowledge inscribed on stone, regardless of reason.

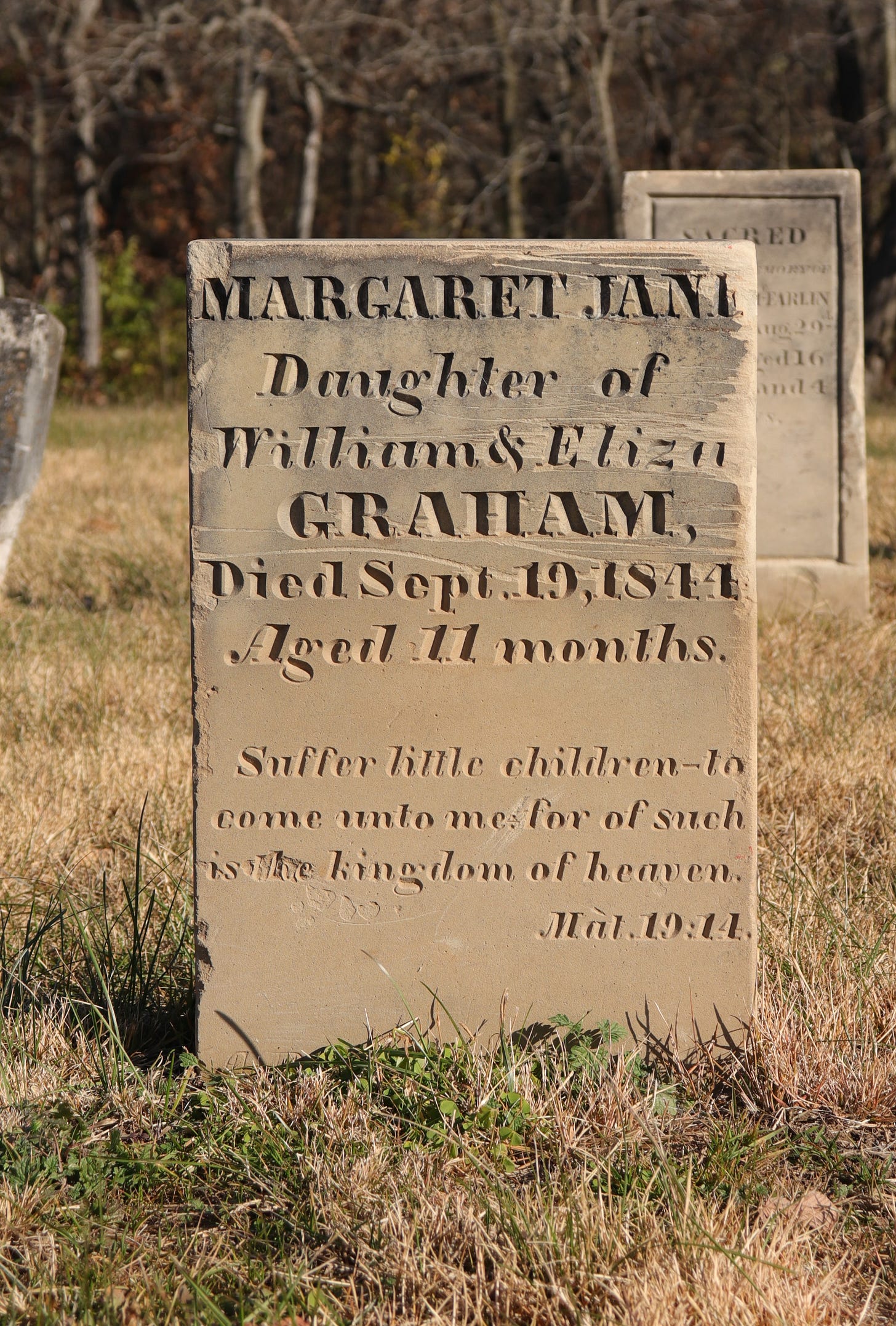

Suffer Little Children

The number of nineteenth century child burials is astounding. During mid nineteenth century at least 20 to 30 percent of children died before the age of five!5 The grave marker below for Margaret Jane Graham exhibits the classic child’s epitaph from Mathew 19:14. One year old Margaret was the daughter of a Presbyterian minister who briefly pastored at the original 1831 Union Church. When his pastoral assignment changed, his family left little Margaret behind, the only Graham buried there. I was able to track down the resting place of her other family members and link her FindAGrave memorial to theirs. At least in the virtual world, she is no longer left behind.

This stone was identified by style as carved by Aaron Potter from Hamilton Ohio. The full story of Aaron Potter, can be found in:

Aaron Potter, stone carver

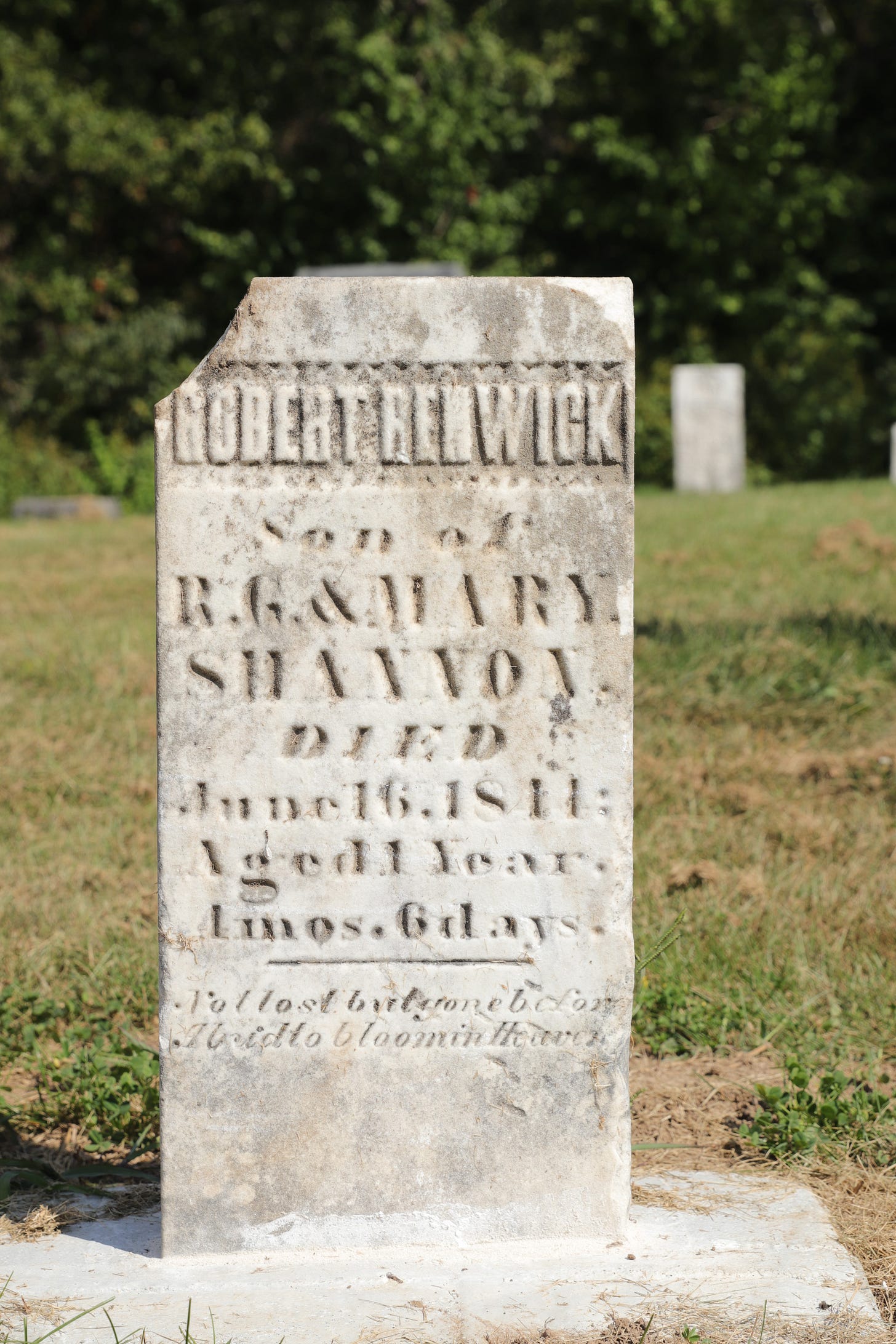

We see Victorian poetry on child grave markers such as this one for little Robert Shannon who also died in 1844.6 There are many poetic versions of this same theme of a flower cut short before it blooms, an apt analogy for a child’s death.

Not lost but gone before, a bud to bloom in heaven.

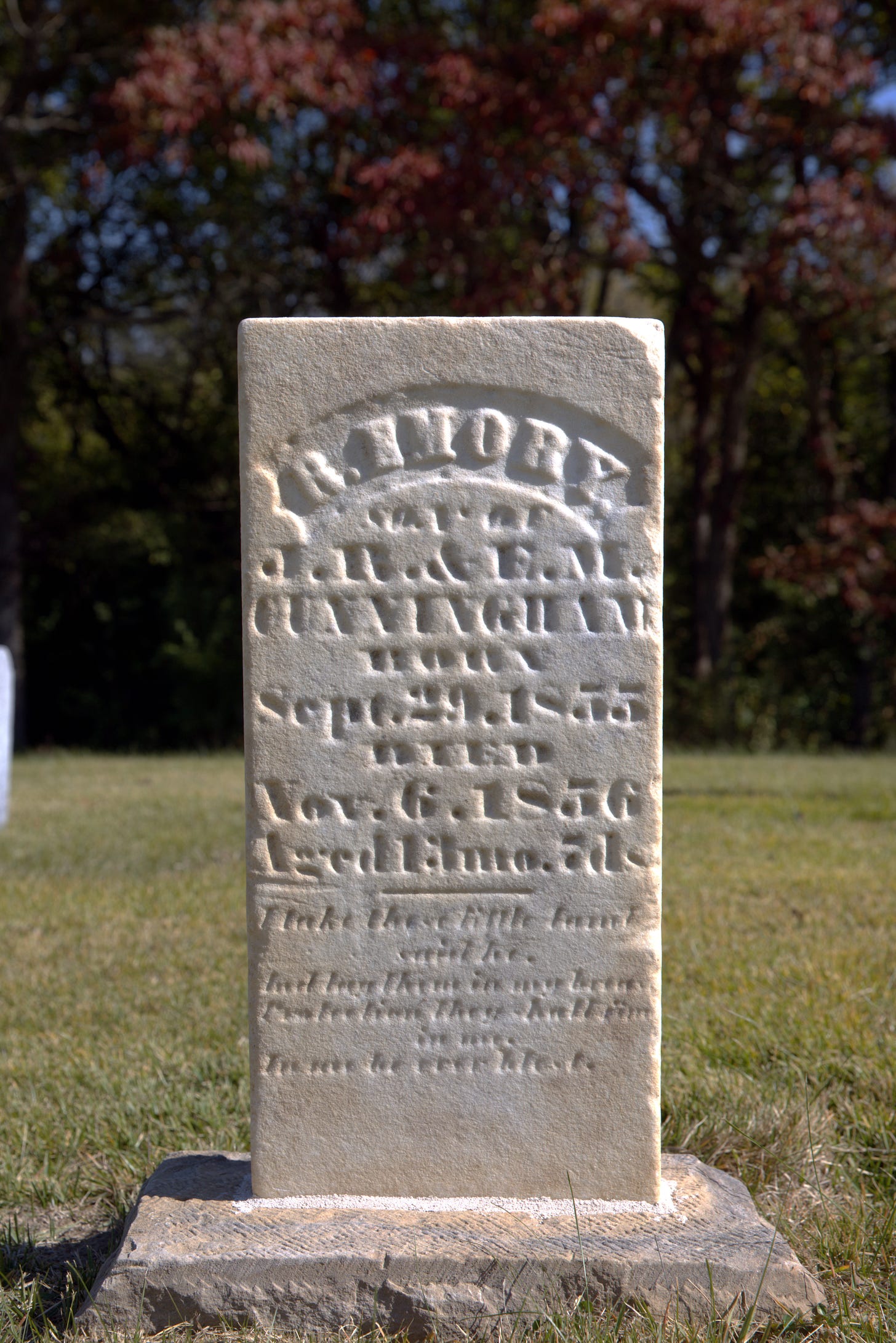

The epitaph below is from a hymn written by Samuel Stennett (1727-1795) titled Funeral of a Child. This epitaph is the third stanza of a five stanza hymn and is found in numerous Methodist and Baptist hymnals. Dating from the late eighteenth century this is one of the older sources used as an epitaph at Union Cemetery, other than Shakespeare and Pope.

I take these little lambs

said he.

And keep them in my breast

Protection. Thou shall live

in me.

In me be ever blessed.

Saddest of all is an infant that did not live long enough to even receive a name. These are just identified as INFANT or sometimes INFANT SON or INFANT DAUGHTER.

Presbyterian Anthem

Below is the monument for revered Presbyterian minister Alexander Porter (1770-1836) found at Hopewell Cemetery, Preble County, Ohio.7 There are several versions of the story of how he led the Scots-Irish8 out of S. Carolina to the promised land of Preble County, Ohio. The biblical pretensions of this story weaken a bit when you realize many of the Carolina Irish were already in Ohio and voted at Hopewell Church (Israel Township, Preble County, Ohio) in 1813 to raise money for his salary and send for him.9 Nevertheless, Porter was a dynamic leader and had a profound impact on the lives of his congregation.

Many of his Hopewell congregation later moved on to Randolph County, Illinois where we see the ripple affects of Rev. Porter’s influence. At least four men buried at Union Cemetery have the middle name of Porter. See below the gravestone of James Porter Patterson (1833-1857).

Perhaps the most lasting influence of Reverend Porter is the dissemination of the bible verse Revelations 14:13. It appears on Porter’s own monument and is also the most repeated epitaph inscribed on the grave markers of the Scots-Irish Presbyterians at Union Cemetery.

"Then I heard a voice from heaven say, 'Write this: Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord from now on.' 'Yea,' says the Spirit, 'they will rest from their labor, for their deeds will follow them.”

John Hanson finds Rev. 14:13 commonplace among the epitaphs found at Congregationalist cemeteries of the eastern seaboard.10 This makes sense as the Congregationalist and Presbyterian denominations were closely connected in the latter eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Both embodied a shared Calvinist doctrine, emerging from the reform of the Church of England. In the 1801 Plan of Union, the two denominations even agreed to share ministers in remote frontier areas.

Abbreviated iterations of this verse exist such as “Blessed are the dead” or “Their works do follow them.” These shorter meme versions are less costly but still convey the message of “the worthy are at rest.” Below is an aphorized version couched in a more approachable style. Not only does this convey the theme of dying a good death, finally getting a good rest would be an appealing idea to the work weary people of that era.

Happy are they who die in the Lord, they cease from their labor and are at rest.

Civil War historian Drew Gilpin Faust11 believes the Civil War carnage was so horrifying that it prompted a secular shift in American culture. Evidence for this is found at Union Cemetery in the brief epitaph “Gone but not Forgotten.” Revelations 14:13 was gradually phased out and is no longer used as an epitaph after 1920 while “Gone but not Forgotten” remained in use even unto the present. Below, Civil War veteran William Morrow has only the terse Gone but not Forgotten epitaph as do many other veterans of the Civil War.

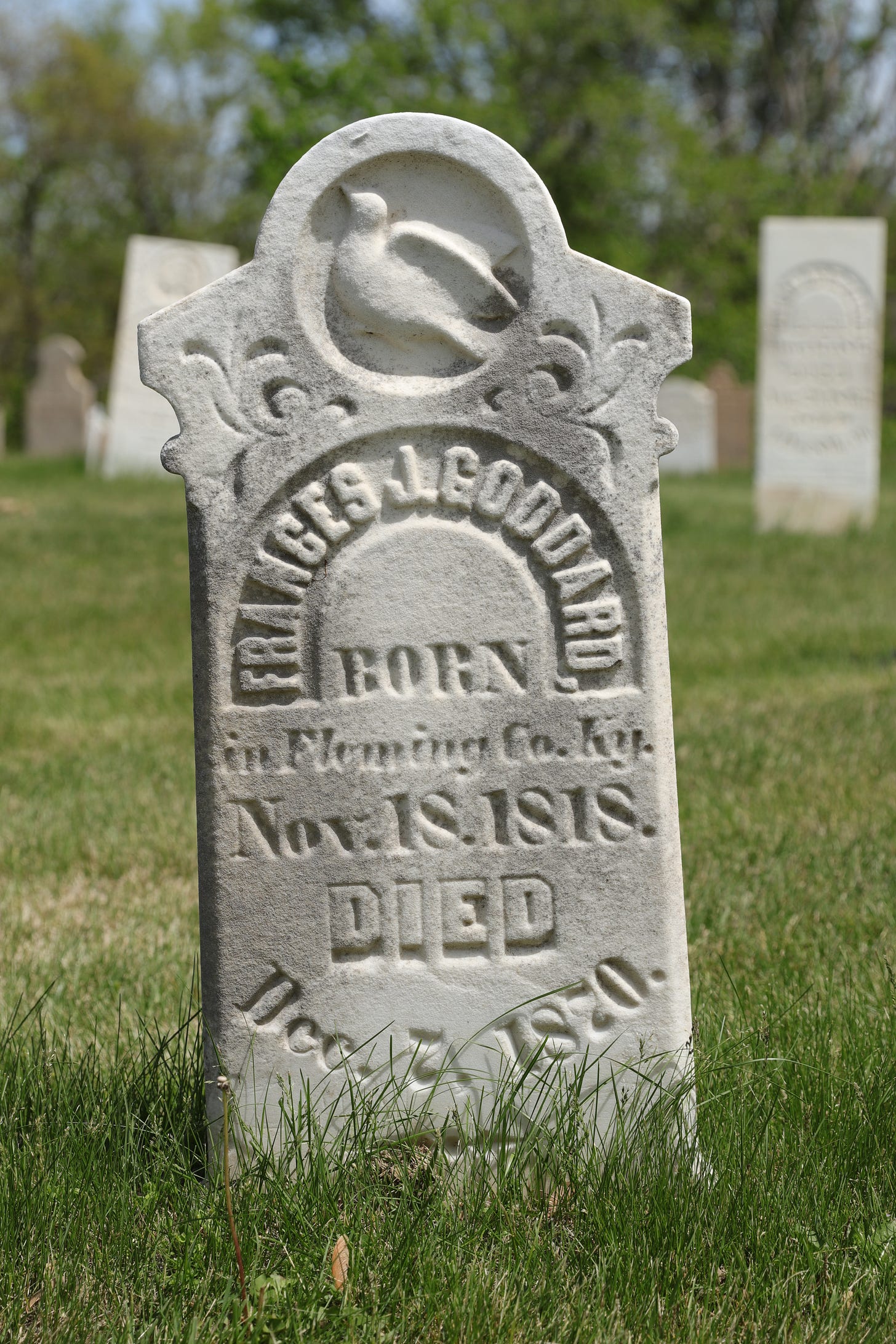

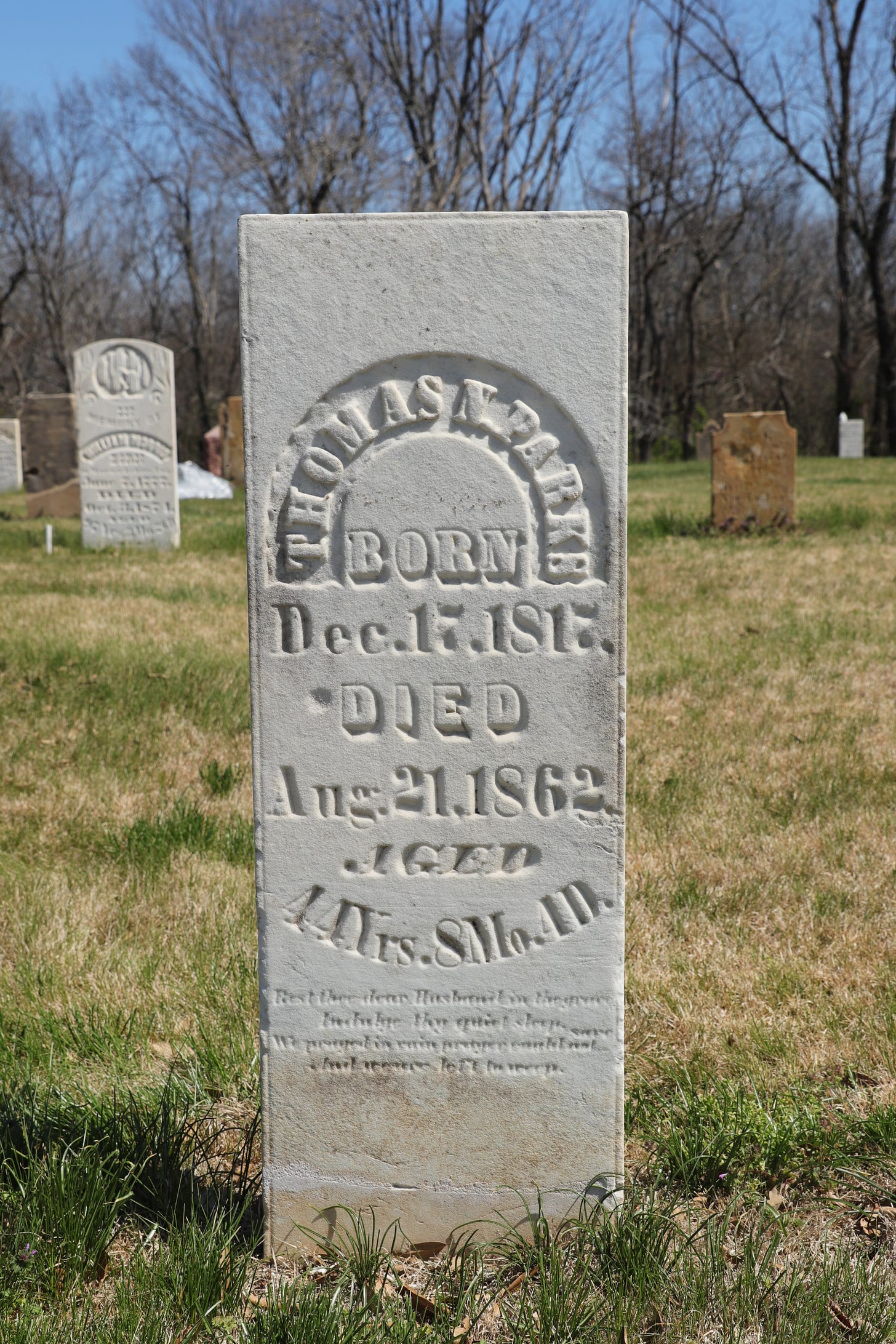

The growing dissatisfaction with religion amid the horrors of the Civil War is shown in this epitaph below for Thomas Parks. It seems a very personal message from his grieving widow, Sarah Ann Morris Parks.

Rest thee dear Husband in the grave

Indulge thy quiet sleep.

We prayed in vain prayer could not save.

And we are left to weep.

Hymn as Epitaph

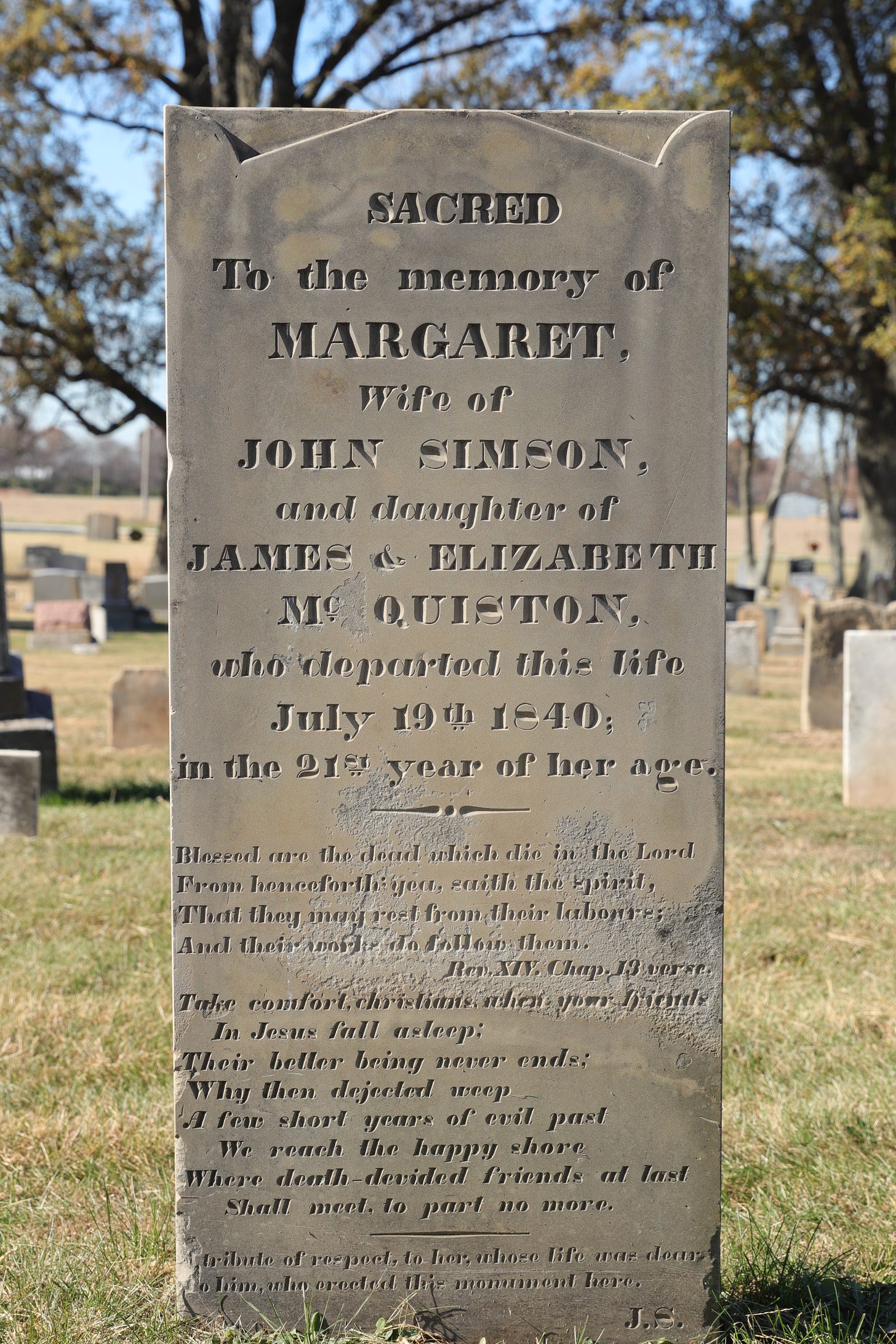

This Margaret Simson monument (below) dating from 1840 is inspired by both the biblical verse Revelations 14:13 as well as the hymn, Take Comfort Christians When Your Friends. This hymn is an excellent example of “paraphrasing” that the Scots and Scots-Irish are well known for. Using 1st Thessalonian 4:13, hymnist John Logan turned the words to a rhyming structure and then set it to music. 12

French composer , F.-H. (François-Hippolyte) Barthélemon (1741-1808) wrote the original score but was later arranged by Robert Simpson (1790-1832, Scottish).13 Of particular interest is that Robert Simpson is from the same town in Scotland as Margaret’s husband John Simson’s (Simpson) grandfather and could easily be a brother. If your great uncle was known for arranging hymns, what better way to honor both your departed wife as well as your uncle who died just eight years previously?

Take comfort, Christians, when your friends

in Jesus fall asleep;

their better being never ends;

why then dejected weep?

Taking Credit

There is a third part to this epitaph at the very bottom.

A tribute of respect, to her, whose life was dear to him, who erected this monument here. J. S.

The J. S. initials obviously stand for Margaret’s husband, John Simpson. Through our modern bias we might see this as a boastful act of taking credit in erecting the monument. The Presbyterian Scots-Irish however, may have viewed this as the embodiment of the values of duty, family loyalty, and community standing. It reflected a culture where death was a public act, gravestones were costly investments, and inscriptions served as lasting records of relationships and responsibilities. Of the three known examples at Union Cemetery of this so called “taking credit,” all are connected to Scots or Scots-Irish with names like McDill, McCormack and Simpson.

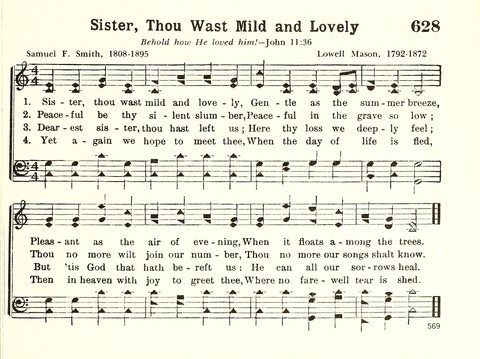

One widespread source of epitaphs is the hymn, Sister, Thou Wast Mild and Lovely which you can hear at this link in piano solo. Click here→ Sister Thou Wast...

This hymn, included in The Psalmist hymnal and published in 1843, remains one of the most popular sources of nineteenth century epitaphs. Several of the stanzas have been used as popular epitaphs.

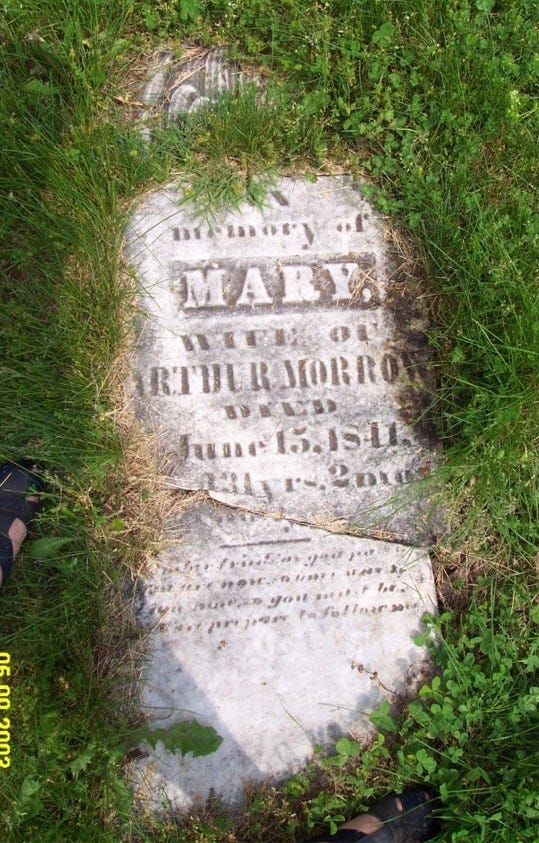

This simple sweet melody has made a comeback in modern times. No wonder it was a popular source of inspiration for epitaphs. Or was it a favorite song of the person whose grave it watches over? How many times did Arthur Morrow hear this same melody at church?

Its popularity as a church hymn has varied in usage but between 1840 and 1890 was quite popular, found in 37% of all hymnals at its peak in 1860.

And again I hope to meet thee

When the day of life has fled

When in heaven with joy to greet thee

Where no farewell tear is shed

Victorian Poetry

I have not yet found a single piece of actual quoted poetry as epitaph here at Union Cemetery. I would expect Tennyson, Wordsworth or perhaps Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Did copyright restrictions deny their use? The majority of epitaphs here are derived from the King James Version Bible or well established church hymns. The epitaphs that do not fit a clear category are conceivably “bespoke” poetry as epitaph researcher, John Hanson describes.14 These anonymous poems seem to be heavily derived from multiple sources into a coherent verse finally making its way into a stone cutter’s book of epitaphs. One such is the following “Dear Willie.”

This world "Dear Willie" was

never fit for thee,

Was never meant thy home to be.

Thou wast to us a season given.

But thy abiding place is heaven.

Some of these verses seem to reflect the Victorian fascination for the occult and after life. Guardian angels, moving toward the light and divine protection are recurring themes. The epitaph below is typical of this genre.

I'm not alone dear ones.

I know a form of light

A blessed guardian

angel, is round me

day and night.

Advice for the Living

The tradition of Memento Mori is also found at Union Cemetery. I was previously told of its existence but until this past year it remained elusive to our search. The epitaph was finally located on a heavily damaged marker as shown in the photo below from 2002. The marker is in worse condition today.

Remember friend as you pass by

As you are now once was I

As I am now so you must be

Therefore prepare to follow me

The inevitability of death, as represented in Memento Mori is an old tradition going back to the European middle ages. This general theme is well documented and occurs in various forms over hundreds of years, both in Europe and North America. In the version below, we see Victorian poetry customized for a young man who likely died suddenly from the cholera epidemic of that year. The epitaph seems fitting for a young man abruptly struck down.

Sweet faded flower,

There you lie.

Let it warn the youth,

That they may die.

A unique presentation of Memento Mori is shown below on this marker for Samuel Morris, carved by his father William Henry Morris (1777-1874), an amateur stone carver in Randolph County. William, English born and immigrated to the U.S. at age 12 had familiarity with English writers such as Shakespeare, Alexander Pope, and in this case moralist writer Hannah More (1745-1833). This marker is located in Brazeau, Missouri but is connected to Union Cemetery where the majority of William Morris carved markers are found.

Below, a close up of the epitaph. Unfortunately, an ill advised “restoration” was done in the past using poured concrete which has obscured the bottom of the inscription.

Reader who [ever you]

Are, who h [ave neglected]

To remember [that to die is the

En] d for witch [you were

Bo] rn. know, that you have

A personal interest in this

[Sce] ne. turn not away

[From] it in disdain however

[Feebly it may have been

Represented]

Hannah More (1745-1843) a well known moralist and playwright in her day, is today an obscure character of English literature. What she lacked in quality was compensated for in long winded quantity. Moore wrote on a wide range of topics such as how a man should choose a wife (actually good advice), arguments for the emancipation of slaves and nearly every religious topic imaginable. The gravestone carving of William Morris15 is associated with only four literary sources, Shakespeare, Pope, the Bible and Hannah Moore.

Reading Epitaphs on the Edge of Existence

Despite all the tricks of lighting and cyber analysis, there is still a threshold beyond which neither the human nor digital eye can see. As marble stones melt under acidic rain and weathering climate, there's a race to preserve these words in stone. If you're transcribing cemetery markers, don't stop at names and dates—capture the voices of the past while you still can. The epitaph for Carolina Foster, below, is too far gone. We are too late.

A fact of life is that you can only do so much. So I will take inspiration from Sarah Hawthorne Morrow, my 2nd cousin three times removed. Sarah’s epitaph reads simply:

She hath done what she could

I use a 7000 Lumen Braun rechargeable.

Formalized death certificate reporting in Illinois began in 1916. While earlier attempts at recording vital statistics existed, they were inconsistent and lacked enforcement until that year.

This stems from the European system of coverture, a legal doctrine by which the legal rights of a married woman were subsumed by her husbands.

The French phrase ancien domicile literally translates as former residence, but to the Scotch Irish, this term is also descriptive of cultural identity.

Preston, Samuel H., and Michael R. Haines. Fatal Years: Child Mortality in Late Nineteenth-Century America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991. In 1800, child mortality may have exceeded 50 percent, but lessening to 15 percent by 1900. This improvement is attributed to scientific understanding of disease transmission, wealth accumulation and adequate plumbing. Vaccinations made little impact.

1844 was the year the village of Kaskaskia washed away by the flooding Mississippi River. The unusually heavy rainfall combined with flooding caused a severe epidemic that summer, presumed to be cholera. Many children and young adults died.

Astonishingly, the church still stands. I received an email this past week from Robert Simpson informing me the church is holding services this Sunday. http://www.historichopewellchurch.org/1806-1834.html

I have chosen to use Scots-Irish rather than Scotch-Irish. The former is more accepted today as the correct usage although you would have heard Scotch-Irish back in the nineteenth century. I prefer not to confuse a noble people with whisky or cellophane tape.

H. L. Leonard Porter III, Destiny of the Scotch-Irish: An Account of a Presbyterian Migration, 1720–1853 (Self-published, 1985).

John G. S. Hanson, Reading the Gravestones of Old New England (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. Publishers, 2021), 57.

Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008).

https://hymnary.org/text/take_comfort_christians_when_your_friend#Author

The details on this verse were identified through https://hymnary.org/.

John G. S. Hanson, Reading the Gravestones of Old New England (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. Publishers, 2021), 23.

William Henry Morris (1777-1874) is the only amateur gravestone carver in Illinois known by name and biography. His grandfather was on the committee in Stratford on Avon that refurbished the Shakespeare funerary monument in the 1740s.

This was an absolutely captivating read. I never thought of gravestones as a form of official record keeping, and always thought of inscriptions more like performative statements. Of course I realize now this is totally wrong.

I like The calculation of age down to months and days underscores the idea that every moment of life is significant in the eyes of God. I have found such precision in German burial registers though not usually in English registers.

I was interested in the tip about the best time of day to photograph inscriptions. Your many clear photos are a great tribute.