Copywrite 2025.

Photos owned by the author might be shareable if you ask permission first.

Part II of a three part series on the Underground Railroad in Randolph County, Illinois.

The Anti-Slavery Society of Randolph county.

One hundred and eighty-five years ago on July 4th, 1840 the Civil War was set in motion at a small Presbyterian church in Opossum Den Prairie, Randolph County, Illinois. Three years earlier, Elijah Lovejoy, Presbyterian minister was murdered by a pro slavery mob at Alton, Illinois some 75 miles north. From this moment, abolitionist groups organized to end slavery, and thus began the twenty year buildup to the shots fired at Ft. Sumter.

The term “meet by adjournment” implies there was an earlier meeting at that location. The wording “general attendance” rather than public attendance speaks that perhaps not all are welcome. Overall, the furtive messaging implies that discretion should be observed.

The use of Union Church as a meeting place for the Anti-Slavery Society was a bold move. The Union congregation was divided on the issue of slavery, so why was the meeting held there?1 Was it a jab at the church members who did support slavery? Or was it a recruiting event to boost membership?

By map, Union was only four miles from Eden, the center of abolitionist discontent. It was also over twenty miles from Rockwood, the first stop on the Eden route. It seems something else was going on here. Perhaps it was a fund raising event. Or maybe it was a deliberately provacative action. We may never know.

Finding Union Meeting House

The exact location of the original church building was lost to memory and rediscovered only recently in 2023. Searching in an area identified via historical records, perpendicular transects were measured out and shallow soil samples taken every two feet. The existence of orange flecks of brick identified the extent of the building foot print. Having the exact dimensions from historical records allowed our conservation volunteers2 to plot it out once we located a foundation corner.

Only the graves and markers of the church members remain to mark the location of the church. In 1869 after the Civil War, the building was torn down and materials re-purposed in the construction of a new church nearby. The Union Meeting House referred to in the above newspaper ad existed from 1832 to about 1869 and no photos are known to exist.

Slave Stealers and Presbyterians

Church membership at Union included those both for and against slavery as the United Presbyterian hierarchy determined to find middle ground. One slave owner was known to be a member and both he and family members are buried at Union Cemetery. In contrast to the tolerant views of the United Presbyterians, Covenanters3 took a radical view against slavery. These “hard shell” Presbyterians were represented locally by the Reverend Samuel Wylie at Old Bethel, a Covenanter congregation in nearby Eden, four miles northeast. His nephew, Adam Wylie, is the person listed as the Secretary of the Randolph County Anti Slavery Society.

Even though a majority of Illinoisans found slavery disagreeable, Randolph County was by majority pro-slavery. Even those opposed to slavery sometimes expressed disdain for the “harping abolitionists.” Everyone had an opinion on the issue but few were committed like the Covenanters.

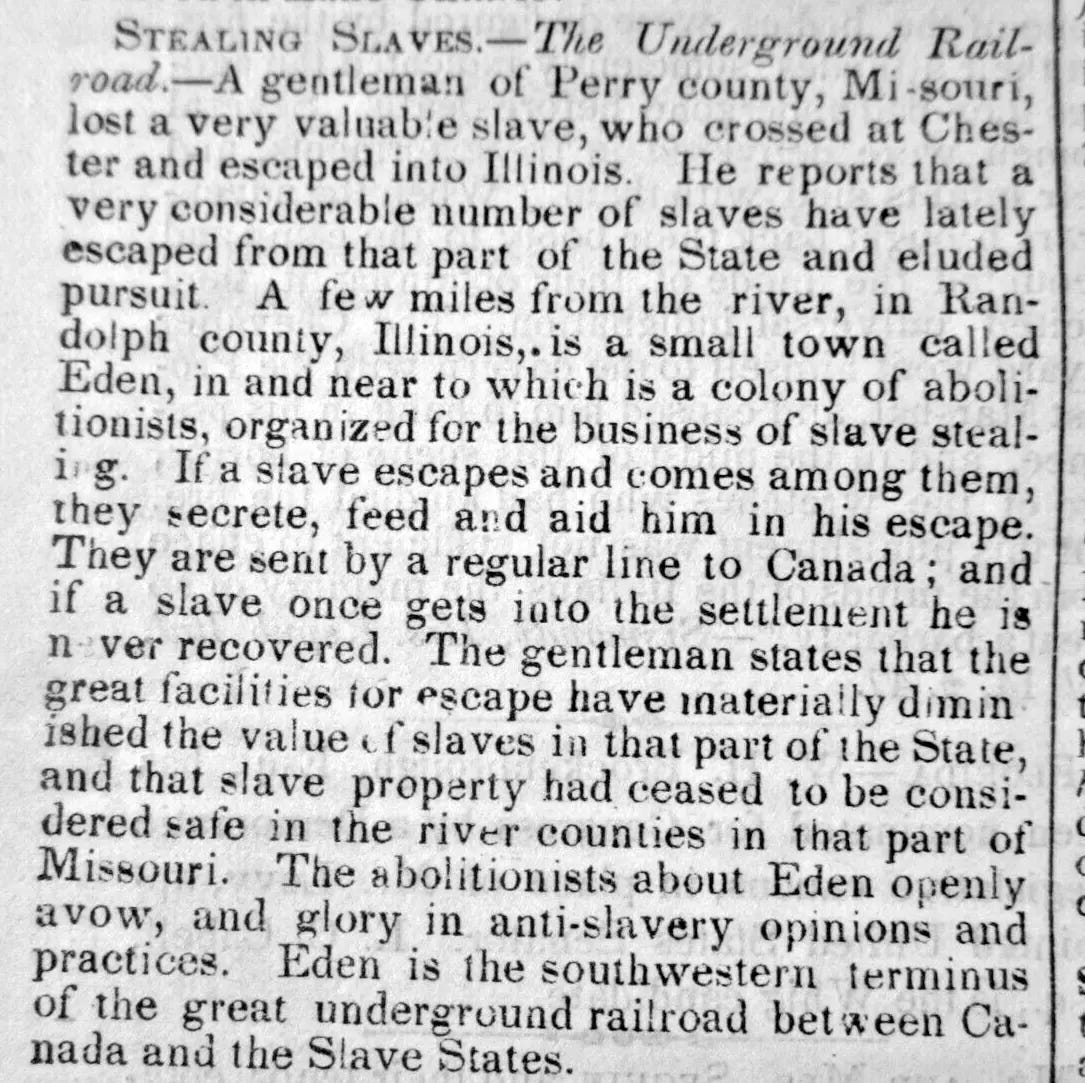

By 1845, the Anti Slavery Society of Randolph County made the national news, forever associated with the term, “The Underground Railroad.” Then as now political activist groups have their own name as well as the name given by their detractors. An abolitionist to one person is a slave stealer to another.

As an indication of the scale and effectiveness of the Eden route on the URR, slave patrols were instituted in Perry County Missouri just across the river. Armed patrols on horseback traveled the roads at night discouraging slaves from running to Illinois. The Missouri Civil War Museum at Jefferson Barracks near St. Louis has an amazing collection of first hand accounts describing this period in detail. This museum is a hidden gem and I highly recommend a visit.4

Eden - a key element of the Illinois Underground Railroad

The small village of Eden emerged as a key hub for one of six major routes in Illinois' Underground Railroad operations. Scots-Irish Covenanters, who settled Eden after fleeing South Carolina’s slavery a generation earlier, vowed to shield their children from its degrading influence. Church membership required an oath to renounce slavery.

The covenanters may have identified with the treatment of slaves because of their own tortured history. There is a display at The National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh. Standing there looking into the display and seeing the torture devices used during the “killing time” of the 1680s, one is left with a sick stomach more than knowledge gained of history. Covenanters were hunted and killed like game. Martyrs were hanged and the stories told from father to son for the next 300 years, the path to my own ears. The given name of Renwick is found in my family tree, derived from the martyr, James Renwick.

Eden’s strategic location on the main road north, near a large slave population in Perry County, Missouri, across the Mississippi River, made it a key crossing point for runaway slaves into Illinois, particularly around Chester. Eden, not shown on the map, lies two miles east of Sparta in southwestern Illinois.

The Seibert map is an amazing historical document but at times is only a crude approximation of actual freedom routes based on long ago remembered events.5 A more granular analysis reveals that instead of towns like Chester and Sparta, the actual routes were often rural, in caves and farm sheds and then finally a run for it in a wagon covered in hay. The routes were also at times ad hoc, changing during the 25 year period of 1835 to 1860.

Juneteenth or July 4th?

While it is gratifying that Juneteenth exists as a separate holiday to mark slavery's demise, it demonstrates shallow understanding of our nation's history. Worse still, it minimizes the efforts of slaves to set themselves free.6 Look at the map above, the URR existed largely within the confines of the free states. Runaway slaves still had to find their own way through the slave states of Missouri, Kentucky and others.

July 4th since 1776 has always been the most pivotal day of the year in American freedom movements including:

The anti slavery movement pre-Civil War,

Post Civil War African American celebrations

Women’s suffrage movement7

So tomorrow give some thought to an idealistic young man named Adam Wylie who set out to change the world on July 4th. Have a great holiday in celebration of our nation and its imperfect but ongoing quest for freedom!

In part III we will explore the structure and details of the Eden URR line.

If you missed part I you can find it here:

https://serengenity.substack.com/p/the-underground-railroad-still-has

Please hit the ❤️ button at the bottom of the page to help this story reach more readers. And if you’re not already a subscriber, I’d love to have you join me. Thanks!

Pirtle, Carol. Betwixt Two Suns, Carbondale & Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 2000.

Union Cemetery is organized as a Non-Profit 501(c)(13). Volunteers provide the labor and energy for conservation and interpretation of historic features here. https://www.facebook.com/UnionCemeterySpartaIllinois

A Covenanter was a Scottish Presbyterian who adhered to the National Covenant (1638) and Solemn League and Covenant (1643), pledging to uphold Presbyterianism and resist religious and political interference by the Stuart monarchy, often leading to armed conflicts during the 17th century.

Missouri Civil War Museum, https://mcwm.org/visit/location/

Siebert, Wilbur Henry. The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom. New York: Macmillan; London: Macmillan, 1898.

Foster, Robin R. 2025. "The Truth About Juneteenth: Were They Waiting—or Fighting for Freedom? They Weren’t Waiting in 1865—They Were Fighting in 1863." Genealogy Just Ask Robin (blog). June 23, 2025.

Post-Civil War African American Celebrations (19th Century):

After the Civil War, African Americans in the United States, particularly in the South, transformed July 4 into a celebration of their newly won freedom following the abolition of slavery. This shift began in the late 1860s, with communities holding parades and gatherings to mark emancipation, reflecting a reappropriation of the date to signify personal and collective liberty.

Women’s Suffrage Movement (1876):

On July 4, 1876, members of the National Woman Suffrage Association, including Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, presented the “Declaration of the Rights of Women” at the Centennial Celebration in Philadelphia. This act linked the date to the fight for gender equality and voting rights, challenging the original Declaration’s exclusionary scope.

Anti-Slavery Movements (1854):

On July 4, 1854, abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison and Sojourner Truth held a rally sponsored by the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, where Garrison publicly burned the U.S. Constitution and Fugitive Slave Act, protesting the nation’s failure to extend freedom to enslaved people. This event underscored a critique of July 4’s ideals.

My Cleland family were definitely Covenenters