The Black Cholera Returns

In June of 1849 twenty year old Lizzie Canady felt the first symptoms of cholera. The sudden watery diarrhea sent her running for the outhouse. The uncontrollable urges came back with regularity every twenty minutes or so over the next hour at which time she began retching large amounts of watery vomit. Apart from the watery expulsion from both ends of her body she did not feel too bad. There was no fever or nausea, she just just kept expelling fluids. Hours later Lizzie became confused, not noticing her shriveled hands, sunken eyes and blue lips. Five hours from onset of the first symptom she was dead. Her last thought had been about the trip to town the day before. The following month twenty year old W. A. Canady also came down with cholera lasting seven hours before succumbing. The Black Cholera had returned to Clinton County, Illinois.1

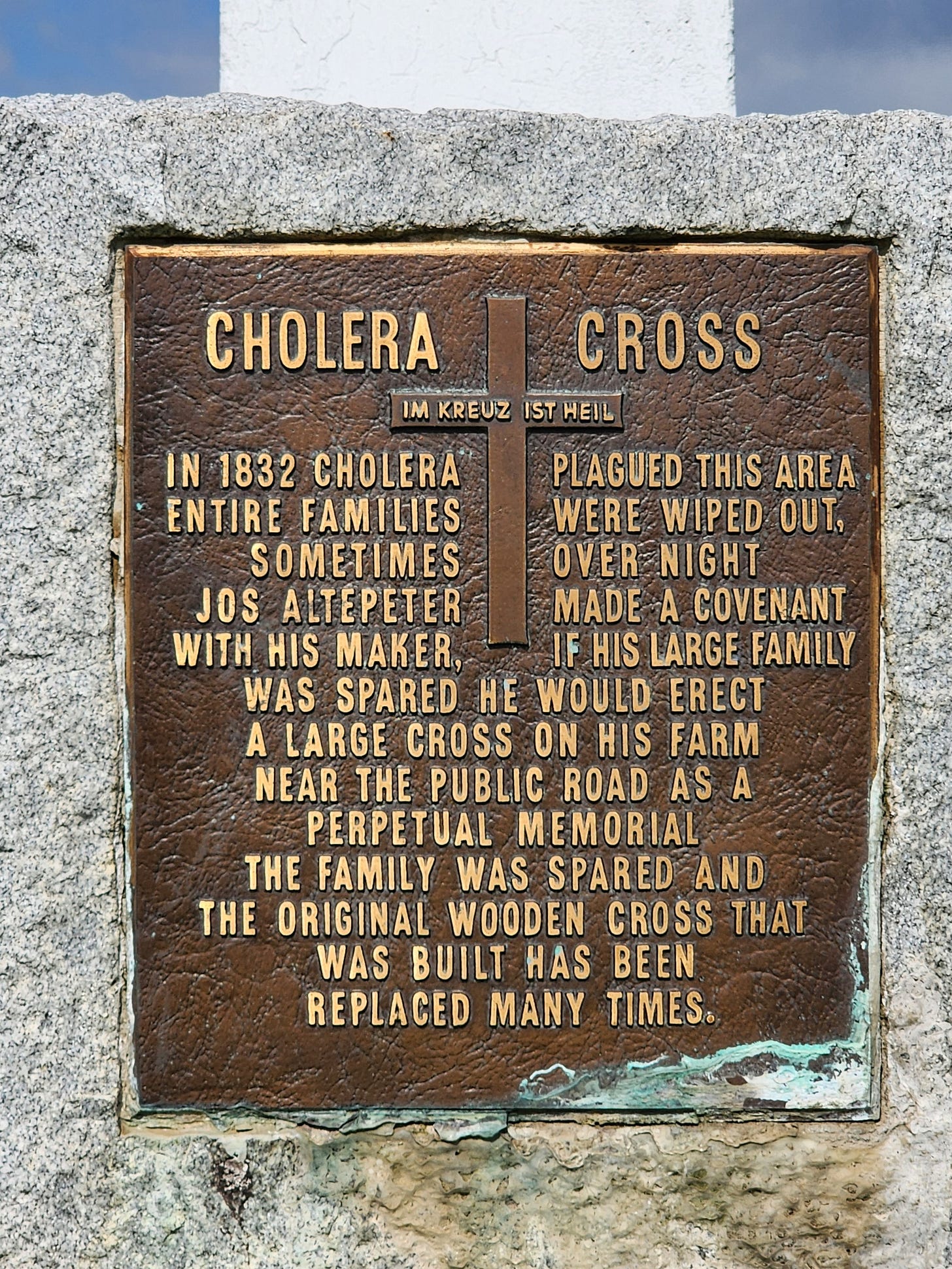

There were three major waves of cholera in the Midwest, the first in 1832 and again in 1849 and 1866 each lasting a year or two. After 1832 the disease was endemic, never really going away but in a reduced state merely plucking a life here and there, nothing like the wave of death, fear and panic of 1832-1834. But in 1849, it came roaring back instilling fear in those that remembered the horror from 17 years earlier.2 In response to the return of cholera, the Altepeter family erected a 25 foot tall wooden cross on their property located a mile south of Breese, Illinois on Germantown Rd.

The story of the Cholera Cross

Through a chance meeting with local Clinton County man who was seeking an artisan to repair his German great grandfather’s marble grave marker, I learned of the story of Henry (Heinrich Joseph Altepeter 1803-1866) and the Cholera Cross. On my drive home, I found the monument as described to me.

There is more to the story than the bronze plaque, which I suspect is true of all bronze plaques. The oral history of local folks contends that the cholera contagion was spreading fast but that it stopped right there, right where the cross was erected on Henry Altepeter’s farm. Emotionally affected, Henry vowed to raise a cross in honor of the God that had spared his family.

In the Cross is Salvation or IM KREUZ IST HEIL

Was the story true?

The claim that the cholera plague that spread from Asia to Europe, jumped an ocean and kept on going throughout North America had stopped right on Henry Altepeter’s farm was too much. I assumed this was the exaggeration of a story told too many times. But maybe there was more to this story.

A year has come and gone since I first laid eyes on the Cholera Cross. In the intervening time, this tale has mulled in my head while I’ve written and researched other cholera related narratives. Then an idea took hold. I realized there was a way to examine the story in a quantitative manner.3 The answer lies within the 1850 census.

First, some research assumptions:

There are few quantitative records for the original 1831-1834 epidemic, but the 1850 mortality census might make a useful surrogate database.

The records are segmented by county and to get a numerical value representing the intensity of the epidemic, I could use the percentage of cholera deaths as a percentage of total deaths.

The variation in severity of disease incidence would correspond to observable factors that would explain the variation.

Cholera is one of the easiest diseases to diagnose due to the distinctive symptoms and rapid onset so that the diagnosis in the census could be trusted.

I would have to research the Altepeter family story itself for discrepancies and alternate versions.

The 1849 cholera scourge by the numbers

There were few diseases of the time that progressed from first symptom to death in six to eighteen hours. On rare occasions, people would hold on for a few days but overall, death from cholera progressed astonishingly fast. An incubation period of one or two days meant someone could travel to a contaminated water source and return home before it hit. The symptoms are acute diarrhea, vomiting, and severe dehydration leading to sunken hollow eyes. The epithelial cells of the intestines are expelled in a way that resembles rice water or tapioca pudding. Any doctor of the day would not confuse the symptoms. Many of the Clinton County cholera deaths progressed in as little as six hours. You feel fine at breakfast, but you are dead before supper time!

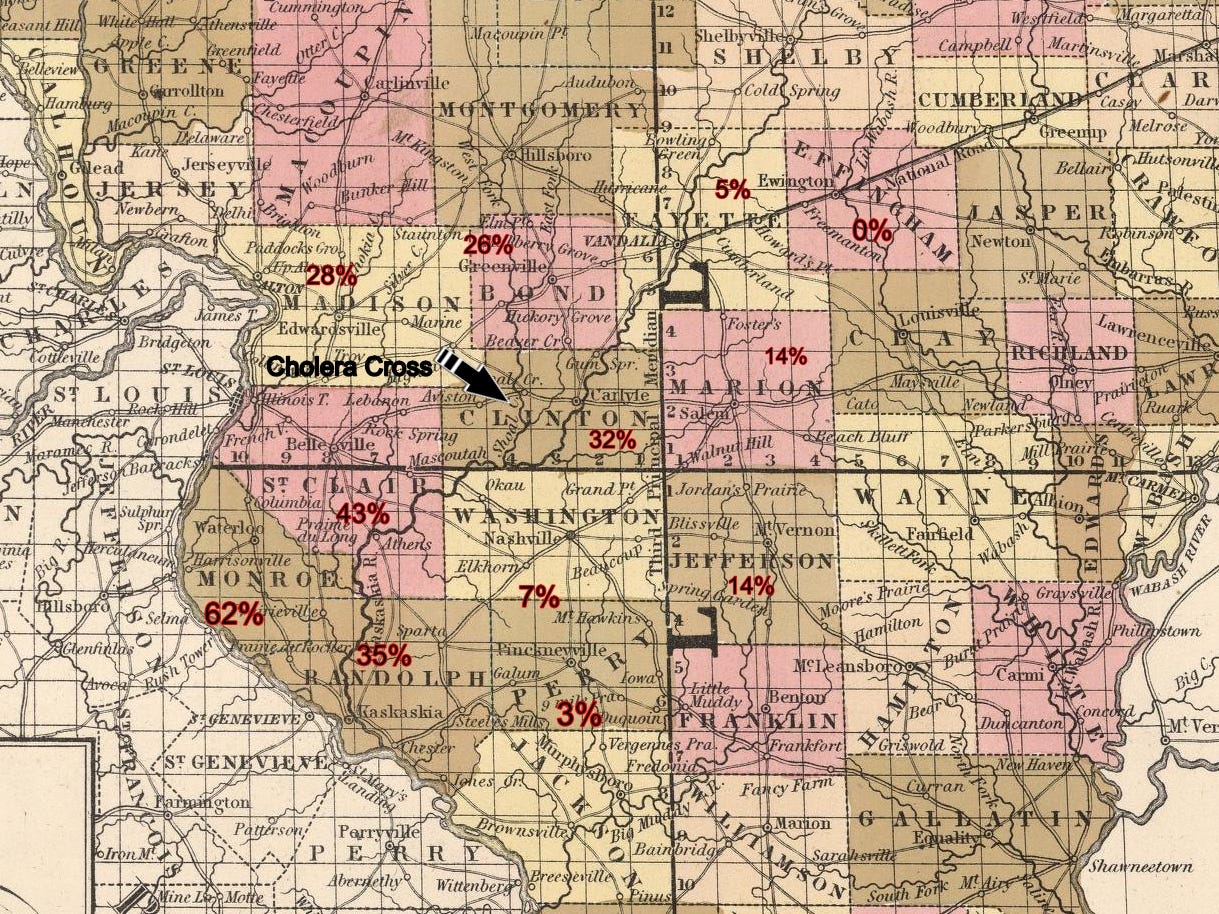

In the map above, the red percentage numbers reflect what percent of total deaths in each county were attributed to cholera for the period June 1, 1849 - May 31, 1850. The navigable portions of the Mississippi and Kaskaskia Rivers were obviously contaminated as were shallow wells near those polluted rivers. But in Effingham County you were more likely to die by horse kick than cholera!

A confluence of transportation routes, population density and polluted water were necessary to create a disastrous outbreak.

The Kaskaskia River was just as polluted in Washington as Clinton County but the Washington county seat of Nashville was far from the Kaskaskia River and relied on deep wells for its water, thus reducing the cholera extent to only 7%.

The 5% number for Fayette County (Vandalia & the upper Kaskaskia R.) appears relatively benign until you dig deeper and realize that 80% of Vandalia’s residents left to get away from the cholera, perhaps they just died somewhere else.4Alternatively, it’s possible cholera had not yet spread to Vandalia by the census collection end date of May 31, 1850.

Carlyle in Clinton County was at the locus of two major transportation routes, the Vincennes trace5 and the Kaskaskia River. With the polluted river water and shallow wells combined with a constant flow of people, it was natural for an outbreak to occur at this location.

If anything, the county numbers reported above are understated. The census taker for St. Clair County explains…

“It has been impossible to obtain the exact number of deaths for the year ending on the first day of June 1850 owing to the fact that the cholera which prevailed as an epidemic took off whole families no one being left to tell the mournful tale.”

— Levi Sharp, Asst. Marshal

There were competing theories about how cholera spread but the prevailing idea was that a miasma (airborne contagion) spread the disease. Did it just spring up out of the soil? Some of the 1850 mortality census pages contain margin notes that give insight into the thinking of the time. There seemed to be a preoccupation with the general land and soil type.

In the Randolph County mortality census, there was the astute (and likely correct) observation that the majority of cholera victims clustered in Chester near the Mississippi River. The significance of which is that the area near the Mississippi held the location of the County seat and the ferry to cross into Missouri. County residents would need to travel to Chester for a variety of reasons, so if the Mississippi was polluted with cholera, Chester would be a place likely to contract the disease. The riverport town of Chester had regularly scheduled stops in 1849 at the peak of inland waterway steamboat traffic.

Chester is situated on and under the bluff on the Mississippi with a broken and hilly timber country back of it. The water used in Lower Chester is taken from the river, in upper Chester from wells impregnated with lime. Most of the deaths by cholera were in Lower Chester. — John Parks, Asst. Marshal (census collector)67

In that same vein of thought, if we examine Clinton County, the predominate fixture is the county seat of Carlyle situated on the Kaskaskia River. The reason Carlyle exists at that exact point is that there is a shallows where the river is easily crossed. The river is still navigable by small watercraft from Carlyle upstream to Vandalia but larger craft would travel no further upstream than Carlyle where they would stop to unload before making way down stream. Today the area of the river upstream from Carlyle is inundated by Lake Carlyle.8

A seeming mystery is why Clinton county would have cholera deaths of 32% but the neighboring county of Washington south of the Kaskaskia River only 7%. The answer may lie in the source of water. Carlyle was drawing it’s water directly from the Kaskaskia R. as well as nearby shallow wells while Washington County’s seat in Nashville drew its water from deep wells generally. The data is painting a clear picture. The larger navigable rivers were polluted while other water sources were not or at least not as much.

Another point to keep in mind is that the dynamic of cholera is that there are infected water sources that people are traveling to. A common scenario in Clinton County is that people would travel to Carlyle for shopping and business, return home later that day, then fall seriously ill. The disease does not really spread, so much as people unknowingly travel to the disease and bring it home, mirroring the conclusions of the famous pump handle experiment of Dr. Snow.9

Anecdotal evidence from Randolph county supports this idea as well. Young adults Jane and Newton Morris fell ill and died from cholera on the same day in 1834 while other members of the family were untouched. Was it because the two siblings traveled to Lower Chester ten miles distant and drank the water while there? Did Jane talk her brother into hitching up the buggy for a ride to town thus sealing their fate?

In the case of Henry Altepeter, his source of salvation may be the happy circumstance that he and his family stayed on their farm rather than traveling to a source of contagion. The 1860 farm census describes his impressive farm operation. He owned well over 200 acres, 14 horses, 5 milk cows, 30 head of beef cattle, 60 hogs and 18 sheep. His farm crops in order of quantity were corn, wheat and oats. The value of his cattle was estimated at $800, an amount equal to that of the most prosperous farms in the area. With a large operation he and his family were fairly well tied down at their farm keeping it all running.

The story falls apart

The Altepeter family story that claims they survived the 1832 cholera epidemic and built a cross in 1850 falls apart under scrutiny. The 18 year delay between the 1832 epidemic and the building of the cross in 1850 seems unlikely. Census records from 1850,10 1860, and 1870 as well as land purchase records, and a ships register from 1839 11indicate Heinrich Joseph Altepeter (1803-1866) and his children were born in Germany and were not in Illinois during the 1832 epidemic. Further, in the Marion and Clinton County 1881 history, it clearly states the Altepeter family came to Clinton County in 1838.12

What really happened

Heinrich Joseph Altepeter came to America around 1838 and did not endure the cholera epidemic of 1832-1834 in Clinton County, Illinois. Is it possible he experienced cholera in Germany? Or was there a bout of cholera in 1844 Clinton County? Both are possible. The details to the Altepeter story are jumbled but in a way, this improves the story.

I believe the Henry Altepeter family lived through the 1849 instead of the 1832 cholera epidemic and did not wait 18 years to put up the cross. That delay of action never made sense. He promised to his God and his family to erect the cross and he did.

This then makes the data in the above map more relevant as it is concurrent with the Altepeter story. From the Illinois map above, it is clear that the main waterways were the prime carriers of the disease. Cholera was killing up to 10% of the population in some nearby towns. In the 1849 cholera epidemic the waves of fear swept up the Kaskaskia River leaving death and panic in its wake.

Riverboats of the day had rudimentary toilets on board. These "water closets" or "heads" were basic facilities, often located on the deck or in a small enclosed area. They consisted of simple seats or benches with holes that discharged waste directly into the river below. Smaller river boats had no facilities at all and relied on emergency stops along the river bank. Cholera only killed about one third of the infected. The other two thirds were spreaders of the disease and particularly devastating was the dispersal of infected waste via the riverboats’ toilet system. If a river was navigable, it was infected with cholera.

Did the cholera stop at Joseph Altepeter’s farm?

We can’t say that it stopped right at his farm. But it certainly seemed that way to Henry. His farm was located only a mile south of where cholera was taking lives daily, yet his family was spared. There is also a clear attenuation of the epidemic as it spread from contaminated rivers into the surrounding areas of higher ground. The headwaters of the Kaskaskia were relatively spared compared to the navigable downstream portions of the river. As I absorb the details this epidemic, I am more inclined than not to believe the cholera scourge stopped just short of the Altepeter farm.

Did God save Henry Altepeter’s family?

In a way the story is true. It was his faith that dampened his fear. Instead of fleeing like the panicked people of Vandalia, Henry stayed on his farm, drank water from a clean well and prayed. Whether you believe God saved Henry’s family or it was only luck, there is still a lesson to be learned. The first thing taught in a wilderness survival book is that if you are not in immediate grave danger, stay calm and stay put. And that’s what Heinrich Joseph Altepeter did.

The Cholera Timeline

Time After Infection Symptoms/Events

0–5 Hours No symptoms yet (incubation period begins).

6–12 Hours- Sudden onset of profuse watery diarrhea (“rice-water stools”)

- Vomiting begins (watery, without nausea)

- No fever

12–24 Hours- Severe dehydration: dry mouth, sunken eyes, clammy skin

- Muscle cramps

- Extreme thirst

- Rapid pulse

- Little or no urine

24–48 Hours- Hypovolemic shock: low blood pressure, cold extremities

- Sunken face and blue lips/fingers

- Possible confusion or unconsciousness

48+ Hours- Death likely without rehydration

- Survival possible with fluids (rare in 1849 due to limited treatment)

Ancestry.com. U.S., Federal Census Mortality Schedules, 1850-1885 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. A portion of this collection was indexed by Ancestry World Archives Project contributors.

Daly, W.J. The black cholera comes to the central valley of America in the 19th century - 1832, 1849, and later. Transaction of the American Clinical Climatological Assoc. 2008;119:143-52;

The cliometric approach to historical research is a method that applies quantitative techniques, economic theory, and statistical analysis to study historical events and processes.

Peck, J. M. (1855). "Cholera in Illinois in 1849," as cited in Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Vol. 41, No. 4 (December 1948), pp. 426–427.

The Vincennes Trail, originally formed by migrating bison, was a major overland route used by Native Americans, European traders, and American settlers. It ran from the Falls of the Ohio (near Louisville, Kentucky) through Vincennes, Indiana, and extended westward to Kaskaskia and other points in Illinois, including Cahokia.

Ancestry.com. U.S., Federal Census Mortality Schedules, 1850-1885 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. A portion of this collection was indexed by Ancestry World Archives Project contributors.

In an odd coincidence I realized as I am writing this that just yesterday my team was repairing the fallen grave marker for John Parks’ son Thomas McDill Parks who died in 1852 at age 14, likely due to cholera.

I was once the hapless passenger in a catamaran that flipped completely upside down with the mast stuck firmly in the bottom muck of the lake. The fickle winds and currents have caused the drowning of many people over the years. I am not a fan of Lake Carlyle.

In 1854, Dr. John Snow traced a London cholera outbreak to a Broad Street pump, mapping cases and linking them to contaminated water. Removing the pump’s handle reduced cases, proving cholera’s waterborne transmission and advancing epidemiology.

Ancestry.com. 1850 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009. Images reproduced by FamilySearch.

Original data: Seventh Census of the United States, 1850; (National Archives Microfilm Publication M432, 1009 rolls); Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29; National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Ancestry.com. New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S., Passenger Lists, 1813-1963 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2006.

Original data: Selected Passenger and Crew Lists and Manifests. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

History of Marion and Clinton Counties, Illinois. Philadelphia: Brink, McDonough & Co., 1881.

Really interesting strategy to figure out the progress of an infectious disease.

My family in Quebec City was devastated by the 1832 cholera, which killed thousands in the city. The reason I know why almost all of them were cholera victims was that the dates of their deaths were in the time window of the first wave of the epidemic and they were all buried in the Cimetière Saint Louis, which the city opened to consign the bodies of people who died of cholera (later for victims of any other infectious diseases). Tallying and analyzing the burials in that cemetery would be a good piece of historical research on the epidemic.

(Not so) fun fact: the Grosse Ile quarantine station in Quebec, which was the port of entry for well over a hundred thousand Famine Irish, the ancestors of six million people of Irish descent in North America today, was actually built in 1832 to control the spread of cholera from immigrants.

What a fascinating explanation of the ways cholera moved across the landscape - or rather how the people transmitted it. Great research, sleuthing and piecing this history together in such a clear and understandable way. Thanks!