The Book as Map: Charting a Families Migration

Clues from Tägliches Hand-Buch Reveal Migration from Württemberg to Russia to America.

Provenance

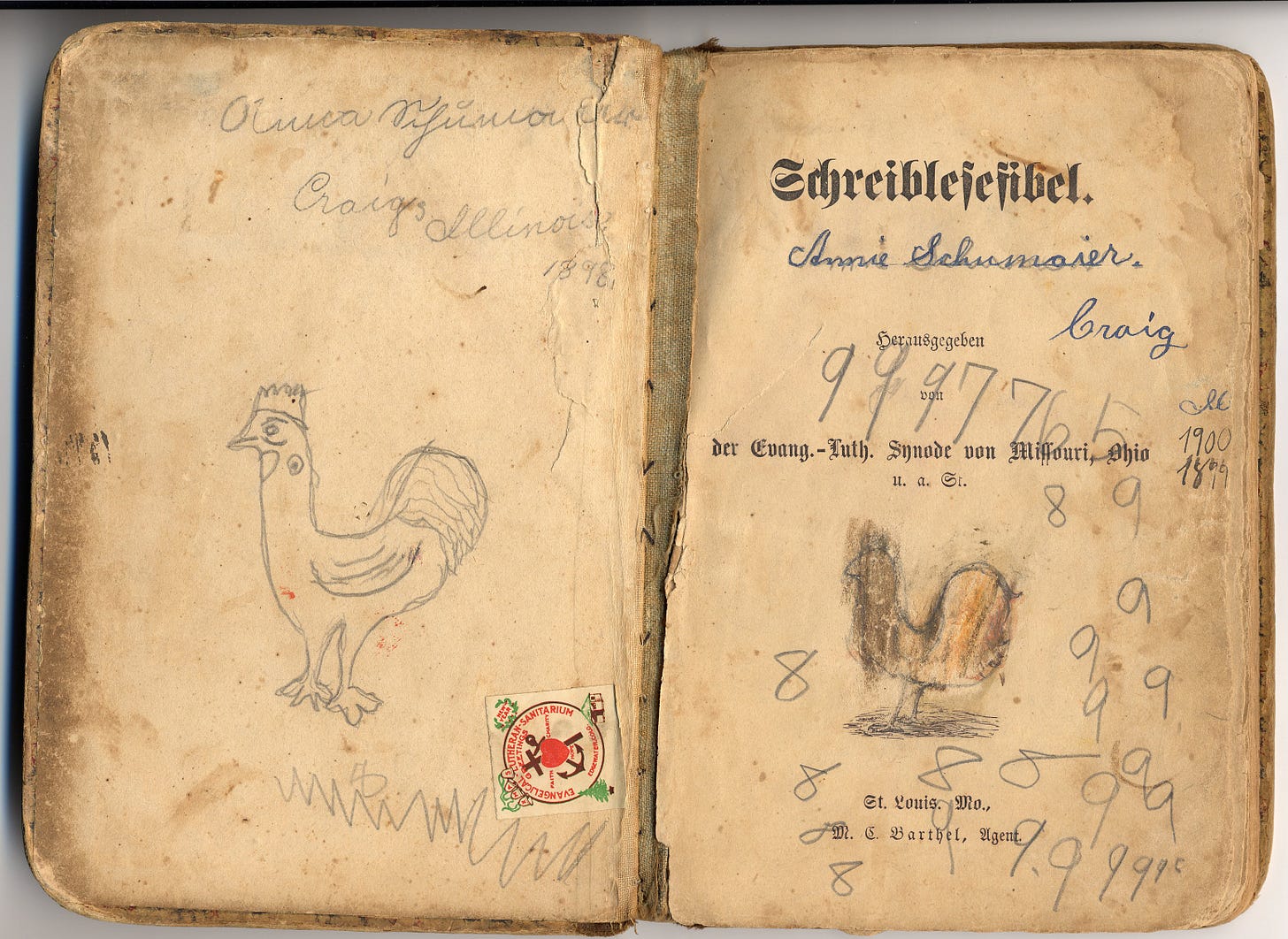

My mother’s mother was embarrassingly old world “Dutchy.”1 She was a second generation German immigrant living in two worlds. She spoke English of course, having been born in rural Perry County, Illinois in 1886 but grew up in a household that spoke German as its first language. Anna’s greatest disappointment was being excluded as a German school teacher because of the trend then to discourage German schools and to anglicize German children as quickly as possible. America after all is a melting pot, voluntary or otherwise.

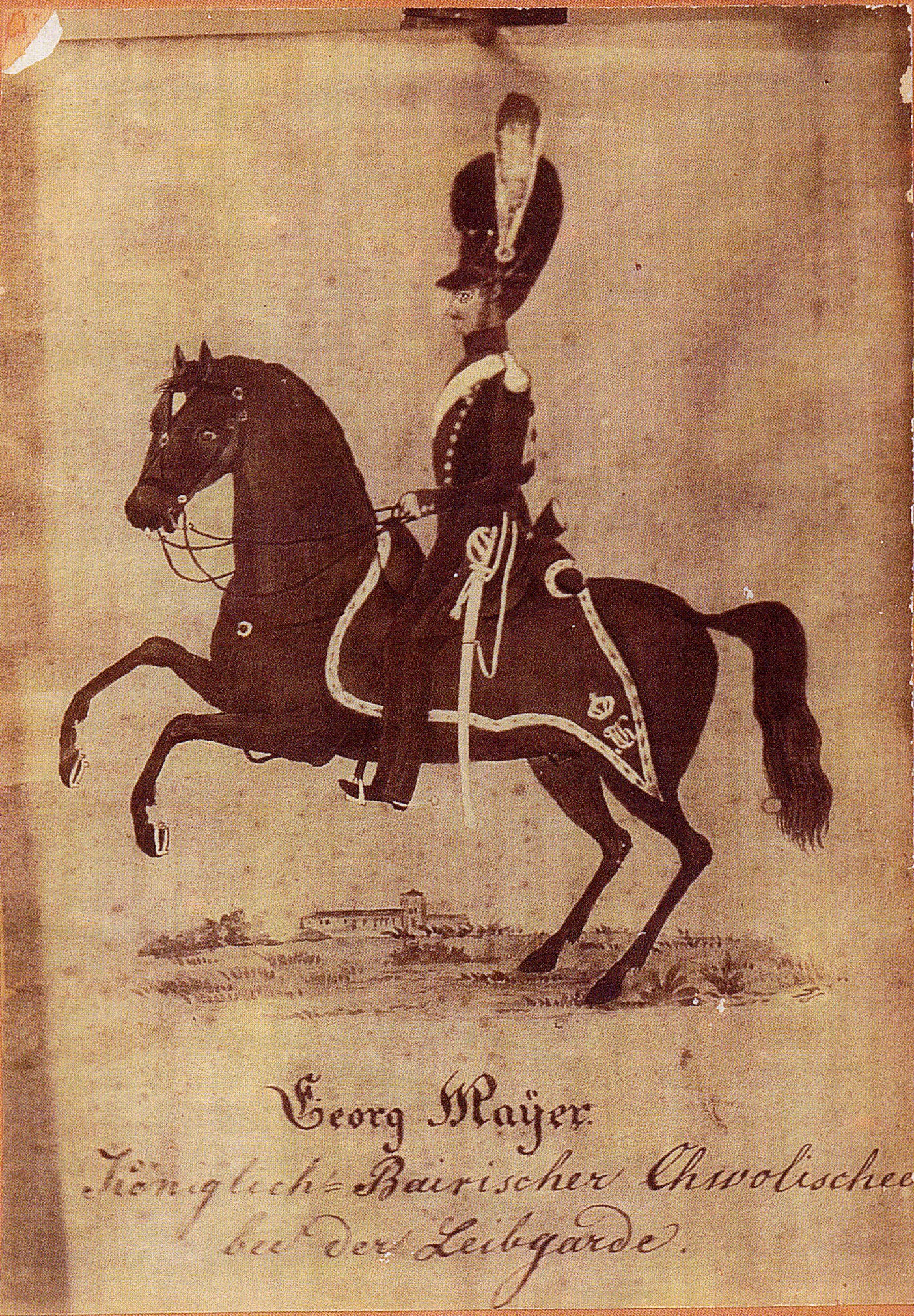

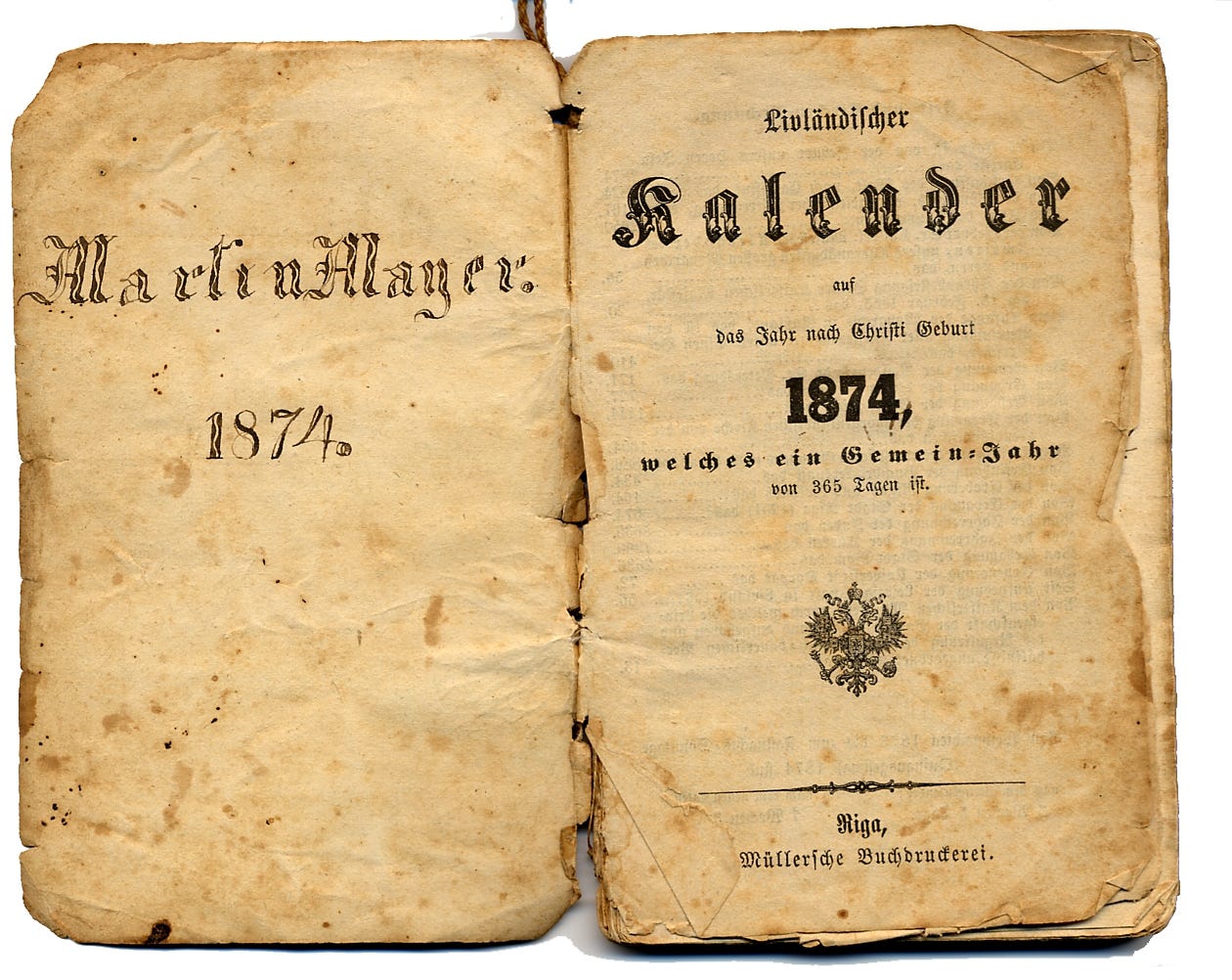

Her parents and older sister Elizabeth immigrated from Sarata, Russia in 1874 to the Perry County, Illinois area of “Brush Prairie” or Craig, Illinois.2 Their mother, Karolina Maier Schumaier was born in the village of Sarata in Russia near what is today Odessa in Eastern Ukraine. Karolina’s father, Johann Martin Maier, had been born in Haunsheim, Bavaria, a village on the border between Bavaria and Wurttemberg. His father, Georg Maier also born in Haunsheim, was a soldier in the Bavarian army that fought for a time under the command of Napoleon during the ill fated invasion of Russia in 1812. He was designated as Elite Guard Light Cavalry and yes he survived.

There is a commemorative Obelisk located in Karolinenplatz, Munich dedicated to the 33,000 Bavarian troops that perished in the disastrous 1812 invasion of Russia. Georg Mayer was one of the 3,000 that survived. The odds of surviving as a Bavarian soldier in the 1812 march on Russia were about 8%, the same as drawing two pair or better in five card stud. That was truly a winning hand considering that construction crews in Poland are still unearthing mass burials from that doomed expedition.

The image below is a copy of the wood plaque presented to him in honor of his service. It reads Koniglich Bairischer Shwolischee bie der Liebgarde or Royal Bavarian Light Cavalry Elite Guard.3 Note the small image of Wartburg Castle under the horses belly.

Pinckneyville

My grandparents house was only a bit better than a shack. It was in the town of Pinckneyville, not far from railroad tracks used by my grandfather to commute to work on the Missouri Pacific RR. My childhood memory recalls the house smelled of coal dust and knockwurst with an undertone of mothball. A coal and wood burning stove, situated in the middle of the main room, heated the house. It was surrounded by comfortable rocking chairs, one of which resides in my formal living room today. But for me, the best part was the trunk.

Tucked away in the bedroom (there was only one) was a camel back trunk that was used to transport the contents of my grandmother’s family from the old world to the new in 1874. She inherited the trunk with it’s books and memorabilia while her brothers inherited farm land. I recall as a child riffling through the assorted books, letters and ephemera. There was a post card from the 1904 worlds fair, books in German and a host of other things mysterious to a ten year old inquisitive boy. Although I have a few things from that trunk, I would give a great deal to have it all as I remembered it then.

The books included a diary of my grandmother’s grandfather recounting their 1874 immigration to America. There was also the Schumaier family bible with inscribed dates of marriage, birth and death. And then there were other books, religious in nature and written in the German language.

The books were later moved from my grandparents house and stored in our attic, scalding hot in the summer and bitter cold in winter which was not a good place for books. After the death of my mother, the family house was sold and the books migrated to storage in a pole barn.

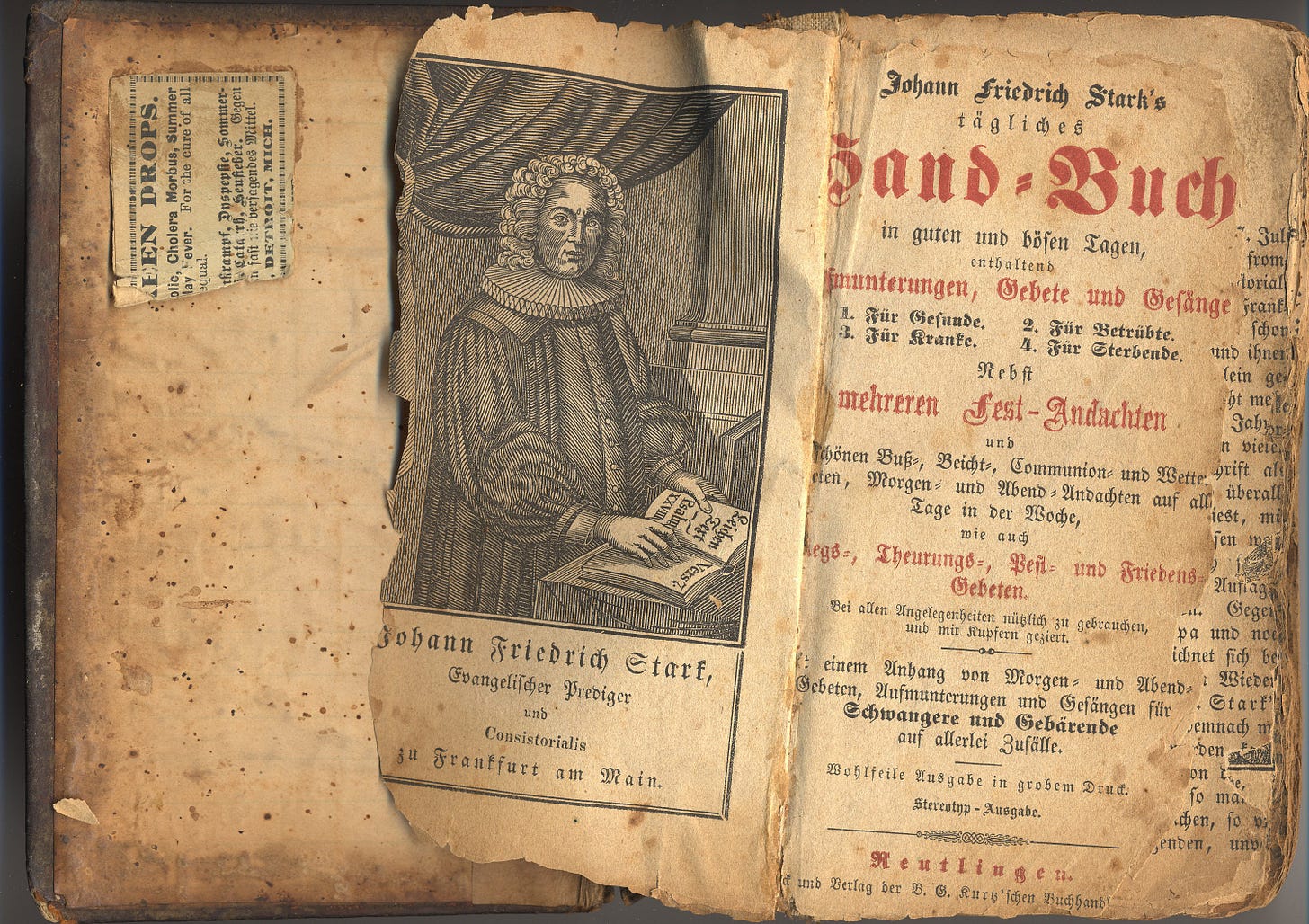

And somehow through all of the years, I managed to hang onto those books. Then several years ago I actually looked at them. Clearly the oldest and most enigmatic item was Tagliches Hand Buch by Johann Friederich Stark. I was holding a gem and did not yet realize the significance.

Tagliches Hand Buch

This is one of the most important and widely published books of the Reformation. Most are familiar with Martin Luther nailing his 95 theses to the door of Wittenberg Church in 1517. Not as many know of Johann Friederich Starck’s Tagliches Hand-buch (for good days and bad days) first published in 1728. If you think of the Reformation as a populist movement that gained control of organized religion, then Starck’s book was the final work that put a do it yourself guide into the hands of plain people.

Instead of a clergy as intercession to God and interpreter of his words, anyone could read for himself the bible now. But the bible was at times confusing and contradictory. The Starck book then filled that need with practical ideas for interpreting the bible and putting Christianity into every day use. It is not too far to say this was one of the more popular “do it yourself” books of that period.

It is not surprising then that Starck’s book ended up in that trunk of prized possessions that went from Haunsheim, Bavaria to Sarata, Russia, and then the 5,000 mile journey to Craig, Illinois, then bounced from house to house for a few decades and today sits in my study wrapped in protective acid free paper.

The book measures 7 X 4 1/2 inches and 1 1/2 inches thick. It is clearly not a first edition and is not in good condition. A date of July 17, 1756 is found in the preface along with a place name of Reutlingen. Reutlingen is likely the publishing location and is located about a hundred miles west of Haunsheim, Bavaria. July 17, 1756 was the 100th anniversary of Starck’s death indicating this edition may have been published in observance of that event. There were over 60 editions and reprints were issued well into the mid 1800’s. This edition likely dates between 1756 and 1820.

With unclear provenance the date after 1756 shows a likely purchase by Georg Mayer’s grandfather in Wurttemberg, then stayed in the family as it traveled time and space avoiding war, house fires, and loss in transport to miraculously arrive 269 years later in my library.

But that’s not the crazy part.

The book has been rebound at some point with leather containing the emblem of the Ottoman Empire, the Turkish crescent moon and star. Further, census records of the Village of Sarata reveal a Mr. Mayer who was described as a bookbinder. This is not a widely held occupation today as books are plentiful and casually discarded at thrift stores. But during the early nineteenth century books were few and heavily used. Every village would need a book binder. Was Georg Mayer also a bookbinder? That we cannot say but it was a small village and only one family named Mayer. The book itself bears testimony to being rebound in leather likely sourced from abandoned Turkish military leather. The Turks had suffered military defeats in this part of Russia ceding Bessarabia to Russia with the 1812 Treaty of Bucharest.

Catherine the Great and the Ottoman Empire

German princess, Catherine the Great became ruler of Russia in 1763. One of her lasting initiatives was to populate sparse areas of Russia with German immigrants, especially those possessing farm and craft skills. Her reasons were principally to modernize the backward Russian economy but also to create a buffer zone between Russia proper and the waning Ottoman Empire to the south.

The first invitation was extended to Germans in 1763 offering free land and autonomy in the Volga region. Later offers by Catherine’s grandson were extended to other areas including the Black Sea area (today Eastern Ukraine). Early attempts by Bavarian immigrants to float the Danube R. to Odessa were met with disaster as epidemics killed off as many as a third.

Sometime before 1822 advance men from Russia were again actively recruiting for immigrants in the upper Danube valley in the towns of Dillingen, Haunsheim, Lauingen, and Gundelfingen on der Donau. The offer of free land and governing autonomy was compelling. The appeal extended to married couples only — which reportedly spurred some hasty marriages!

It was in this context that the village of Sarata was created and populated by people from that small area in northern Bavaria. Twenty-nine year old Georg Maier (Mayer), his wife and two small boys formed one of those 70 families that moved to the Russian steppes in a covered wagon in 1822.

The term “White Russian” has been used in various ways at various times including a vodka and coffee liqueur cocktail, and the resistance army that fought the Bolsheviks in the 1916 Red Revolution, but it is also used to describe ethnic and cultural Germans transplanted to Russia. Although there were many German towns in this area of Ukraine, there were also many Jewish communities in other settlement areas. The setting for Fiddler on the Roof is in this region circa 1910.

Immigration to Amerika

Eventually, the Russians reneged on their promises and began to actively conscript young men into the military. This action more than any other prompted German families to leave, most coming to the United States as the Mayer and Schumaier families did. A trickle became a torrent and by 1910 large numbers of ethnic Germans from Russia had poured into the Great Plains area of N. America. The Dakotas, Montana, and Nebraska are today populated by the descendants of those immigrants.

The reason the Mayer and Schumaier (and other related families) ended up in Southern Illinois rather than the Dakotas is quite by chance. A Lutheran missionary was sent from Concordia Seminary in St. Louis to the Bessarabian area near Odessa. Making contact in the village of Sarata, villagers were eager to send their military age sons with him back to St. Louis. Reverend Schock brought Michael Mayer and several other boys with him who later ended up near Pinckneyville in 1872. There is documentation of letters back and forth but unfortunately the letters did not survive. The diary of Johann Martin Mayer excitedly records, “Letter from Amerika!” His son had arrived and was safe, a father’s happiest moment. Michael sent glowing descriptions of Amerika, and then two years later in May 1874 other remaining family members immigrated to Amerika.

The Germans (and Jews) that stayed behind were treated roughly by the Russian government. But Germans are meticulous record keepers so the abuse was well documented. The cultural memory of this time lasted up to WWII, and was yet another simmering resentment that fueled German revenge against the Russians.

The 269 year journey of the Tagliches Hand Buch

Combining the notes from the 1874 diary, the Concordia Seminary record of Pastor Schock,4 the Verna Beck document5 and the clues from the Tagliches Hand Buch, a timeline of movement can be constructed not only for the book itself but the Maier family.

1756 or after - Reutlingen - the Tagliches Hand Buch is printed and purchased by Georg’s grandfather Ludwig Maier who resides in Niederstotzingen, Wurttemberg ten miles west of Haunsheim. Reutlingen is located 100 miles due west.

1756 to 1793 - Georg’s father Johann Martin moved to Haunsheim prior to 1793, the year in which Georg was born.

1805 - The Capitulation of Ulm, in which Napoleon captured an entire Austrian army near the city of Ulm. Twelve year old Georg would have witnessed the trappings of war without much of the violence. Ulm is located only fifty miles west of Haunsheim.

1812 - Georg Mayer enlists (or is drafted) into the Bavarian army. He serves until 1815 and is involved in the Grand Armee march on Russia under the command of Napoleon. Later battles include Leipzig, Hanau and Waterloo. It should be noted that Bavaria switched sides and fought against Napoleon at Waterloo.

1822- Georg Maier moves to Sarata, Russia where he stays until his death in 1858. At age 65 he was jumping his horse over a hedgerow, the horse fell and Georg broke his neck.

1872 - Pastor Schock takes 21 year old Michael Maier back with him to the St. Louis area.

1874 - Maier and Schumaier families immigrate to Craig, Illinois.

It’s just old stuff isn’t it?

I am astounded to find how much can be revealed by the the systematic study of an old book. Or the study of a letter, photo, military award or any number of other artifacts and ephemera. Mostly these items get discarded a generation or two after the significance is lost. That’s why families lose these items. It’s often not the fault of the person doing the discarding though. The blame rests with the previous generation that did not explain what it was.

What artifacts do you have that deserve preservation? Do you know the story? Have you written the story and given it to the younger generations in your family?

Please hit the ❤️ button at the bottom of the page to help this story reach more readers. And if you’re not already a subscriber, I’d love to have you join me. Thanks!

In colloquial use in twentieth century Southern Illinois, Dutchy is an adjective used by English speakers to describe German descendants particularly agrarian, backward people. Dutchy is a derivative of the word German speakers use to describe themselves, “Deutch” or German.

Craig is an unincorporated area today, not much more than a train depot at it's peak located 6 miles northwest of Pinckneyville, Illinois. The area today is referred to as Winkle.

Chwolischee has no known translation relative to the period or in German. It seems to be a colloquial translation of the French “Chevau-léger,” or light horseman. Various internet searches and A.I. point also to “Swiss cheese,” “heavy artillery,” “heavy cavalry” and “Swabian.” Research is ongoing.

Pastor Schock was the missionary sent from Concordia Seminary, St. Louis Missouri to the Village of Sarata.

The Verna Beck document is a pedigree chart taking the Mayer and Schumaier families back to before 1600. It was given by me as a copy from Verna Beck a distant cousin. The researchers name is unknown.

Breathtaking research in telling this whole big story - well done! And what a historically and personally significant artifact.

Fascinating. The book held so many clues that it did function as a map. Brava.