Shakespeare and Pope come to Opossum Den Prairie: a 400 year journey of words.

The traveling words of Alexander Pope and William Shakespeare found their way to Union Cemetery, Sparta, Illinois. But how?

Opossum Den Prairie

The prairie is long gone. Neat corn rows occupy the former haphazard prairie of little blue stem and Silphium. And if you asked a local for directions, they might not even recognize the name. Located in Randolph County, Illinois, Township 5 south, Range 6 west, this is where Illinois began.1

In the northwest corner of section 24, on a ridge separating forest and former prairie, lies Union Cemetery.2 Spanning seven acres, burials date from 1831 and also as recently as a few months ago. This is where I found the words of William Shakespeare (1600) and Alexander Pope (1717).

Click here: Union Cemetery

Betsy Newton Morris (1794 - 1831)

I knew of Betsy’s epitaph before I knew she was my 3 times Great grandmother. Considering she traveled the old pioneer trails west, gave life to ten children, and then died in a log cabin at age 37, Betsy could have been the model for the Madonna of the Trails monument.3 Her grave marker is large, well made, and accompanied by two large rectangular slabs giving the effect of a ledger stone. The stone carver’s name is unknown but the marker is similar to those of the Cincinnati, Ohio area, sometimes found in southern Illinois. The stone itself is Berea Sandstone, sourced from an Ohio quarry. The tympanum is best described as a stylized soul effigy, the incising deep and well ordered. It is professionally made, likely expensive, and a fitting tribute to the tragic death of a mother of ten. The epitaph quietly speaks to us from another time.

BETSY MORRIS

Died January 15th - 1831

Aged 37.

Much loved, once valued,

a heap of dust remains alone of thee;

It's all thou art and all

the proud shall be.

While memory holds a

seat in this devoted breast

of mine, remember thee I will;

William Morris

This epitaph derives from two well known sources. The first is from Alexander Pope (1717) in Verses To the Memory of an Unfortunate Lady,4 and the second, William Shakespeare in Hamlet (abt. 1600) Act 1, Scene 5. Put together in this way they form a coherent poem expressing the brevity of life yet memorializing the departed wife.

Alexander Pope

The Pope epitaph itself is not rare and has been found on two other grave markers nearby; Eleanor Irwin at Old Bethel Cemetery near Sparta and Martha Hemphill at Old Salem Pioneer Cemetery near Lively Grove.

The Eleanor Irvin marker from 1822 is an interesting “bespoke” version. Here the deceased is speaking for herself, rather than a reminder of death directed at the reader. “Avails thee not” becomes “avails me not.”

Many variations on the Pope epitaph can be found all over the eastern U.S. from the coast to Southern Illinois. Because of the number of characters required for this quote (about 132), it is generally found on more substantial (and perhaps costly) grave markers. The earliest I found was on the 1755 Mary Rodgers marker in Mickleham, Surrey, UK, and the most recent was Martha Hemphill, 1839, in Randolph County, Illinois. The further pioneer settlement moved west, the later in time we find this verse on grave markers, suggestive of James Deetz’s Doppler effect.5 Seriation changes through time, are also reflected in the geographic movements of people, culture, and artifacts.

The original quote

The original version of Pope’s verse is found in his 1717 publication.6 In later editions of his work, the words stay true to the original. Alterations of this verse appear to have been done many times and many places but Pope, himself, did not make changes to his own work.

How lov’d, how honour’d once, avails thee not,

To whom related, or by whom begot;

A heap of dust alone remains of thee;

‘Tis all thou art, and all the proud shall be!

Michael Dobson, Director of the Shakespeare Institute addressed this issue of changing literary works in a recent podcast. He notes that plays, such as those of Shakespeare were frequently altered to fit specific circumstances of audience, actors and the mood of the times.7

It’s perpetually asking to be regenerated, translated and spread.

- Professor Michael Dobson,

John Hanson discusses the epitaph he found on the 1784 grave marker for William Dunsmoor in Lancaster, Massachusetts’ Old Settler’s Burial Ground in his book, Reading the Gravestones of Old New England. Notice the misspelling of avales which should read as avails. More significantly the word honour’d has been replaced with valu’d. This change made at least as early as 1755, stays with the quote when found later in time.

How lov’d, how valu’d, once avales thee not,

To whom related or by whom begot;

A heap of dust alone remains of thee,

Tis all thou art, & all that die shall be.

Hanson notes that this epitaph is found in New England in the latter 1700s and as late as 1808 there. He further states that this Alexander Pope verse is found in Murray’s English Reader which may explain its appearance in different times and different places.8 The version above has an edited last line. The last line of the verse usually reads as Tis all thou art and all the proud shall be. Perhaps it was deemed offensive by the family and “toned down” a bit by the stone cutter.

The earliest version of the Pope verse I could find which includes the word, “valu’d” is from 1755 on the Mary Rodgers gravestone in Mickleham, Surrey, UK. Given this early date it appears that changes to Pope’s original version occurred well before Murray’s English Reader publication in 1799. The Mary Rodgers version reads:

How lov’d How valu’d once! avails Thee not,

To whom related or by whom begot

A heap of Dust alone remains of Thee

Tis all thou so timid and all the Proud shall be

I wonder if Mary Rodgers was a timid soul resulting in yet another “bespoke” version of Pope’s verse.

Murray’s English Reader

The version in Murray’s Reader9 was originally published in 1799 with subsequent editions in 1808, 1815, 1829, and 1849. All editions through 1849 read the same:

How lov’d, how valu’d once, avails thee not;

To whom related, or by whom begot:

A heap of dust alone remains of thee;

’Tis all thou art, and all the proud shall be.

The most recent quote of Pope’s verse known to me is found on the 1839 marker for Martha Hemphill and is a verbatim copy of Murray’s English Reader version. It seems likely the English Reader is the direct source of this epitaph.

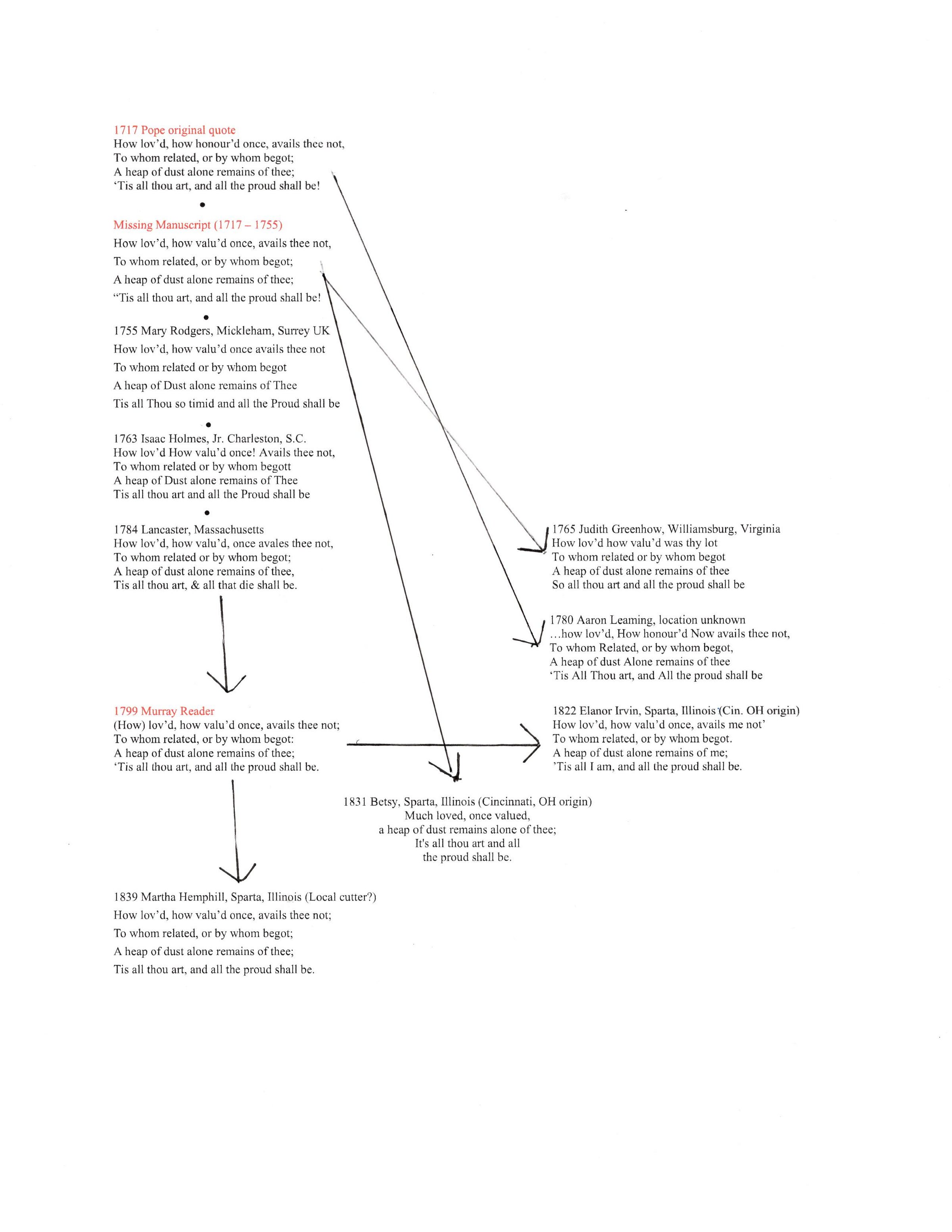

Connecting the dots.

If this information feels confusing or overly complex you are not alone. I determined to make sense of it with with a simple technique. I wrote each known version on small strips of paper and arranged them in chronological order vs deviation from the original quote. This clarified the transmission of the verse over time. Here’s what I found:

There appeared to be three main printed sources:

1) Pope’s original quote from 1717, then republished in 1737.

2) An unknown secondary source that logically must date from 1717 to 1755.

3) The ubiquitous tertiary source of Murray’s English Reader, first published in 1799.

The unknown secondary source is inferential only but must exist, otherwise it is difficult to explain how subsequent epitaph versions after 1755 had changed the word honour’d to valu’d. It is remotely possible this could be explained by “backdating” of monuments erected long after the actual burial. Could the source be the 1799 Murray’s English Reader? This seems improbable given that there are several grave markers on two continents stretching back as far as 44 years before it was published!

The unknown secondary source could be a classroom reader similar to Murray’s English Reader. It may also be a book of Epitaphs in use by stone cutters in England and Colonial America during the period of 1717 - 1755. As additional evidence, the entry in Murray’s English Reader labeled the verse as “Epitaph,” not as an excerpt from Alexander Pope.

It was common for a stone cutter to make bespoke versions of the verse to suit the customer. We see this in the 1765 Judith Greenhow marker, the 1784 Dunsmoor marker, as well as the 1822 Eleanor Irvin marker. Greenhow’s and Dunsmoor’s appeared derived from the unknown secondary manuscript, and Irvin’s from Murray’s English Reader.

Then what of the Betsy Morris epitaph?

Out of all of the examples of the Pope verse, the epitaph on Betsy Morris’s grave marker is not only the most reductive but the most polished. Compare the original Pope verse as written in 1717 with the epitaph found on Betsy’s 1831 marker.

Pope 1717 with 134 characters:

How lov’d, how honour’d once, avails thee not,

To whom related, or by whom begot;

A heap of dust alone remains of thee;

’Tis all thou art, and all the proud shall be!

Betsy Morris epitaph 1831 with 87 carved characters;

Much loved, once valued,

a heap of dust remains alone of thee;

It’s all thou art and all

the proud shall be.

An entire line has been eliminated, the grammar is more modern, and individual words have been replaced. Virtually the same thoughts are expressed but with 35% fewer characters; 87 characters versus 134 in the original quote. Was the editing done only to save money? Or was something else at work?

A less obvious but important change is that the poem has been transformed from a traditional rhyming couplet to a more modern sonnet like structure. The rhyming lines of AABB were changed to ABCB. The staccato of Pope’s original verse is thus changed to a more flowing rhythm.

The use of valued instead of the original honour’d marks it as derived from the unknown secondary source. But the overall heavily edited appearance indicates a very personalized version, whatever the source.

Borrowed Shakespeare

The second portion of the epitaph from Betsy’s grave stone is clearly borrowed from Shakespeare, yet it too has been reduced and altered to produce a more personalized version. No examples of this line could be found in internet searches except for the original line from Hamlet, and the epitaph on Betsy’s grave marker. The implication is that either the stone cutter or William Morris, himself, wrote these lines borrowed from Shakespeare. Given the fact that Morris “signed” the marker, I conclude that those are his words, however they may have been borrowed.

Hamlet, Act 1, scene 5 - William Shakespeare, 1600

Ay, thou poor ghost, whiles memory holds a seat

In this distracted globe. Remember thee?

Epitaph on 1831 Betsy Morris grave marker:

While memory holds a

seat in this devoted breast

of mine, remember thee I will;

William Morris

It is worth noting that Betsy's husband William Morris was raised in Stratford on Avon until age twelve and likely attended the same school as William Shakespeare.10 11 His grandfather, Sam Morris, was on the Stratford town committee that completed a restoration on the Shakespeare Funerary Monument in the 1740s.12 William Morris would have been familiar with the works of William Shakespeare as well as Alexander Pope. He certainly was familiar with the more obscure playwright, Hannah More, since Morris personally carved an epitaph on his son’s grave marker using a Hannah More quote.

The Hannah More quote13 carved on the Samuel Morris (1802 - 1854) marker by his father William Morris:

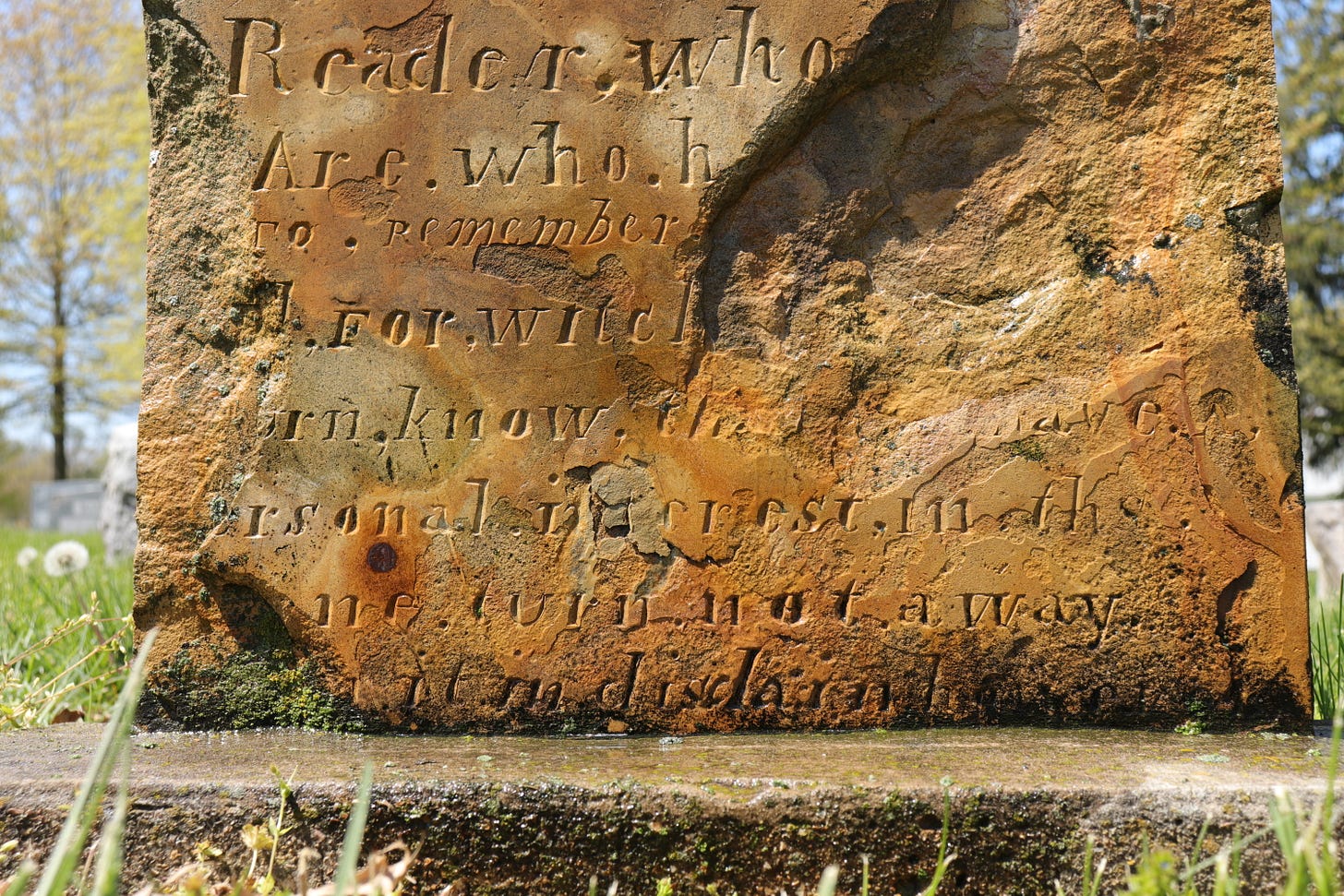

Reader who ever you are, who have neglected to remember that to die is the end for witch you were born. Know that you have a personal interest in this scene. Turn not away from it in disdain however feebly it may have been represented.

I found evidence from census and real estate documents that establish William Morris as functionally literate but not approaching the professional level of an attorney, minister or academic. Notice in the above epitaph, he spells which as witch. Similar systematic errors of grammar, spelling and ordinal indicators are found throughout the other 29 grave markers that he carved. Given that he was uprooted from his home in Stratford and transported to rural South Carolina at age 12 in 1789, it can be reasonably inferred that his formal education was halted at that point.

Here is a link to photos of the thirty grave stones carved by William H. Morris (1777 - 1874) William Morris grave markers

Was Morris the editor of his wife’s epitaph? His amateur stone carving is well documented. His biography places him in Stratford on Avon. His family is connected peripherally to Shakespeare’s family. His grandfather’s connection to the Shakespeare Funerary Monument indicates a family with more than passing familiarity with gravestones. Importantly, Morris also had his name carved beneath the epitaph as if to take credit as the writer.

There is no direct proof that William Morris composed the epitaph on his beloved wife’s grave stone. Yet, the accumulation of circumstantial evidence indicates that he did. Over hundreds of years and thousands of miles, the words of Alexander Pope and William Shakespeare made there way to Opossum Den Prairie. And if you should happen to visit, they are still there, ready for you to read them yourself.

Afterword

And perhaps winning the prize for the most innovative version of Pope’s verse, Pennsylvania merchant, John Mason placed this 1770 newspaper ad in protest of the removal of import tariffs which re-ignited competition from English imports.14

Ah—Liberty! How loved, how valued once, avail thee not

To whom retail’d, or by whom begot,

An empty sound alone remains of thee,

And its all thy one pretended Votaries‡ shall be—

Literally true, the first settlements in Illinois Territory were in Randolph County but “Where Illinois Began” is also used as the county motto.

Union Cemetery is located on Schuline Road two miles south southwest of Sparta, IL. It is approx. 12 miles northwest of the site of old Kaskaskia, the first permanent settlement in Illinois territory.

Madonna of the Trail is a series of twelve identical monuments dedicated in 1928 to the spirit of the American pioneer women. They were commissioned by the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution (NSDAR).

A later edition in 1737 changed the title to the more familiar, Elegy to the Memory of an Unfortunate Lady, but did not alter the verses.

James Deetz and Edwin Dethlefsen, The Doppler Effect and Archaeology: A Consideration of the Spatial Aspects of Seriation, (Southwestern Journal of Anthropology, Vol. 21, Number 3 Autumn, 1965)

Alexander Pope, Verses to the Memory of an Unfortunate Lady, (Printed by W. Bowyer, for Jacob Tonson at Shakespear’s Head in the Strand. 1717) p 361.

"Podcast 10th episode: Let's Talk Shakespeare we ask 'How did Shakespeare get so popular?'" How Did Shakespeare Get So Popular? Podcast, January 10, 2016. How Did Shakespeare Get So Popular?

John G. S. Hanson, Reading the Gravestones of Old New England, (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2021).

Lindley Murray, The English Reader: or, Pieces in Prose And Poetry, Selected from The Best writer, designed to assist young person to read with propriety…. (London: Longman et al. 1799) p 252.

K. E. S. or King Edward VI School has been in service since 1295. William Shakespeare is believed to have attended the school as a boy in the 1570s.

S. L. Morris, The Records of the Morris Family, (self published, 1920).

Morris, Records of the Morris Family, 1920.

Hannah More, The Works of Hannah More, Practical Piety. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1840, chap. XVIII, p. 494.

John Mason, advertisement in Pennsylvania Journal, July 19, 1770.

Bravo! When I first read about the inconsistencies or iterations, my guess was the verses had been memorized and the changes had happened organically. With few books available and fewer still folks fully literate, poems especially were often taught rote, memorized and carried through families like treasured jewels. It would be easy to assume either the family or the carver had simply misquoted the original. Your fantastic research and study of the topic seems to suggest otherwise. As always, great work and thanks for putting this in my radar.

That's really fascinating.