Mt. Tambora: the Eruption that Rewrote My Family's Destiny.

Reconstruction of an 1816 journey from Preble County Ohio to Kaskaskia, Illinois.

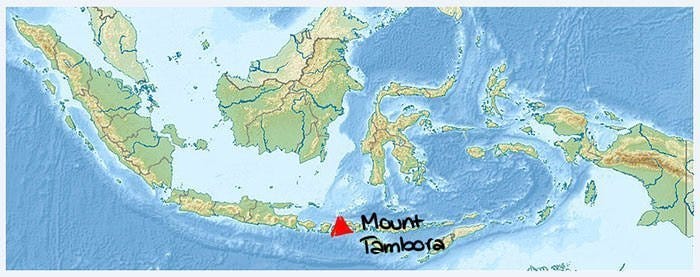

Mt. Tambora

The year 1816 has been humorously referred to as “18-hundred-and-froze-to-death,” but is known more generally as “the year without summer.” Although the initial volcanic explosion occurred on April 5, 1815, it took the better part of a year for the ash to spread around the upper atmosphere. The immediate effects were readily observable as a dry fog or haze. The sun appeared reddish to the extent that some paintings from the period show a pale red sun, as painters painted what they saw.

In Europe there was much complaining of the gloomy skies and seemingly constant rain. Rivers flooded and dirt roads turned to mud. It was a year substantially colder and wetter than normal. The dystopian tale of Frankenstein was written by Mary Shelly during the 1816 summer due to her being holed up through the bad weather at Lake Geneva, Switzerland. In England, we have the painting by John Constable depicting the cold wet weather.

The eruption, coming as it did in the middle of the Dalton minimum1 (1790-1830, a recurring natural cycle of low sun energy), not only plunged the world into cooler temperatures, but it also triggered erratic conditions of precipitation, temperature and sunlight. The net effect in most parts of the northern hemisphere was a shorter growing season and resultant food shortages. Made worse by the Napoleonic wars and the recent upheavals from the War of 1812, the situation was ripe for death, disease and displacement of people on a grand scale. But what was it really like?

The Mt. Tambora eruption was one of the largest in the last 10,000 years and is generally considered “the big one.” The April 5th, 1815, explosion instantly vaporized two cubic miles of rock and pushed an extraordinary amount of debris into the stratosphere. Ultimately, nine cubic miles of particulate matter would be ejected into the upper atmosphere. While the immediate pyroclastic effects killed tens of thousands of people within a 24-mile radius, the lasting impact on global weather killed millions more harmed by famine and related disease. The following is a reconstructed account of how it affected William Henry Morris, my 3rd great grandfather, causing him to leave Ohio for refuge in southwestern Illinois.

Ohio, 1816

January through April

The winter of 1815-1816 was surprisingly mild, so much so that some optimistic farmers began planting crops as early as February, hoping for an early spring. However, on April 18th, a freeze hit central Ohio, bringing temperatures that felt more like midwinter, along with several inches of snow. Then in late April, temperatures reversed, surging into the 80s. While Europe faced exceptional rainstorms, the American experience was marked by cold, dry conditions interspersed with erratic temperatures. The American South, in particular, saw little to no rainfall throughout March and April, and by the end of the month, Ohio was sweltering in high 80s temperatures.2

“We do not recollect to have witnessed a more distressing drought, than that which at this time visits every portion of our country. The temperature of the weather with us is very fluctuating-the evenings and mornings generally so cool as to render a fire quite agreeable. The Earth is so parched…” - American Beacon, Norfolk, Virginia.

For William Henry Morris (1777-1874), 1816 was a make-or-break year. He had purchased his Preble County, Ohio land on Dec. 2, 1813, and as was common of the time had likely made improvements to the land in the preceding year. We only know that he moved from Abbeville, South Carolina sometime after the1810 census and was in Ohio by February 13, 1813, when he married his second wife, Betsy Newton.

Although we do not know the exact motivation for his first move from Abbeville, South Carolina to Israel Township, Preble County, Ohio, there are clues. One account relates that William disapproved of his father’s second marriage “and left taking nothing but the axe from the woodpile.” There was also the condemnation of slavery by the Presbyterian Scotch-Irish inflamed by the fervor of the Second Great Awakening. William was English born but after this time joined with the Scotch-Irish, marrying one of their own for his second wife, Betsy Newton. William’s English father, Samuel Morris Jr. owned slaves, was that a rift between them as well? There was also the lure of cheap land in Ohio.3 Ultimately, for push and pull reasons we may only speculate, William moved to Ohio sometime around 1811.

His 160-acre land purchase was described as a “credit volume patent,” purchased on credit extended by the U.S. Government. In 1813 Ohio, land was typically purchased for two dollars per acre on Government credit at six percent. The minimum parcel after 1804 was 160 acres or 1/4 of a section. One twentieth of the purchase price was due immediately and the balance of 1/4 due in forty days, then 1/4 due before two years, another 1/4 due in each of the two following years. The purchaser had the option to pay it off at any time to avoid interest accumulation. A fifth year was extended if the payments were in arrears. At the end of the fifth year, an arrearage resulted in the government taking back the land and reselling it to someone else. William’s purchase resulted in a payment schedule with all payments and accrued interest due by December 2, 1818.

Dec. 2, 1813 $32

Jan. 11, 1814 $48

Dec. 2, 1815 $90

Dec. 2, 1816 $95

Dec. 2, 1817 $101

Dec. 2, 1818 - arrearage results in foreclosure

From Oct. 11, 1813, until the following April 7, William Morris served in the Ohio militia during the Indian conflict related to the War of 1812. He was assigned during this time to Ft. Brier,4 Ft. Winchester and Ft. Meigs. Importantly, Morris would not have been able to tend his own farm during this six-month period.

Thirty-four years later in a legal deposition filed in order to claim the bounty land due him for his service, Morris states he was “drafted” into the War of 1812 fight. Perhaps he still retained displeasure at being pulled away from his new wife and farm. After a careful examination of his military file in the National Archives, I suspect he may have fought Washington, D.C. bureaucrats harder than the Ohio Indians!

June and July

By June of 1816, William and Betsy not only had one year old Newton and two-year-old Jane to take care of, but Betsy was expecting her third child later that same year. William, along with 14-year-old Samuel, son from his first marriage, worked the farm.

Common crops in Ohio then included winter wheat, winter oats, corn(maize) and a variety of garden crops including potatoes. Also, of course were cattle, hogs, and the family milk cow. In 1816 the corn crop was severely harmed by the shorter growing season as well as the cool dry weather. The other winter grain crops withered away, not receiving the critical spring rains.

Early June was unusually cold over the Eastern United States.

This is an extraordinary spring. On Thursday morning last we had a frost in this city.” - Richmond, Virginia newspaper referring to the early June weather.

After the cold spell in early June, the weather turned more seasonal with high temperatures hitting 80s in Virginia. Then on the fourth of July, another cold wave swept down from the northwest. The Lake Erie area of northern Ohio suffered biting winds with snow in the air. Cooler temperatures prevailed over most of eastern North America. The chief effect was not to outright kill the crops but to impede their growth enough that they would not ripen before the killing frosts of autumn. Corn requires a 120 day growing season and typically longer. In 1816 Ohio, the growing season was estimated closer to 80 days, destroying yields. Some crops, such as wheat and oats that are planted in the fall and ripen in July, were damaged not so much by cool weather as the spring drought conditions. Wheat crops generally fared better than the others. Corn was especially damaged in 1816. The result was a doubling in price as David Thomas reports from his travels through Ohio and Indiana.5

In the 2d month, 1818, the following prices were current.

Wheat per bushel, was $1.00

Corn “ .50

Potatoes “ .375 - .50

Pork, per Cwt 4.50

Beef “ 3.00 - 4.00

The reader will recollect, that in 1816 corn was only 25 cents, and a considerable advance in price, has therefore taken place.

The doubling in corn prices was not the only commodity price increase. The chart below shows overall, commodity prices were on the decline in 1815 due in no small part to the Treaty of Ghent,6 but in 1816 and 1817 were rising again because of the 1816 crop failure.

In Eastern Ohio the hay crop had failed. “Without hay, farmers would either have to slaughter their livestock in the fall or keep them alive through the winter with other crops such as oats and Indian corn,”7

August through October

One early August newspaper account from Baltimore was more optimistic. Due to nearly four weeks of steady warm weather, “the crops of wheat and rye are reported to be as good as usual.”8 That optimism was tempered by knowledge of quite variable local conditions. In Western Pennsylvania, “The crops are thin.” “Hay was a disaster everywhere, and corn could go either way.”

Then on August 20th, a major cold wave extended down from the north bringing frost as far south as Kentucky. In Central Pennsylvania “a temperature, such as is generally experienced in the latter end of October, making thin clothes uncomfortably cool. Cincinnati also suffered heavy frosts.”

By this point in the year, William Morris was facing some hard choices. The crops were severely reduced, depending on the exact grains he had planted. Most pioneers at that time were heavily reliant on corn and that crop was a loss. Betsy was now seven months pregnant, the next mortgage payment was due December 2, and the crops were a disaster. With this, William made the decision to leave for Illinois.

Decision to move to Illinois

The ballooning of debt was significant. If Morris was not able to keep up with any payments after the first $32, he would owe a staggering $382 by Dec. 2, 1818. Likely by June and certainly by August, William’s fate was sealed. The year of 1816 was not going to produce the bumper crop he needed to keep current on his mortgage payments. At some point, Morris made the decision to leave his Ohio farm and join others moving to Illinois. There he could get a second chance with $2 government land on borrowed money.

Not only was a steady stream of people leaving the Northeastern states, but many from Ohio were also leaving for the beckoning opportunity in Illinois. Just two years earlier in 1814, a land office was established in Kaskaskia, attracting surveyors, lawyers, land agents and speculators. Fourteen years earlier in 1802 a group of settlers had moved from South Carolina to establish the village of Preston in Randolph County, Illinois, just nine miles west of the farm Morris would later homestead. Between 1814 to 1818 when Illinois became a state, there was a flood of people, attracted to cheap farmland and a fresh start.

The Illinois Land

William’s brother Richard lived north of nearby Fairhaven, Ohio and while we know little about Betsy’s family, there were several Newton’s living nearby. So, they would be leaving family and friends to start anew in Illinois. By this time in late 1816 there was a steady flow of people from both Preble County as well as South Carolina and Kentucky already moving to Randolph County, Illinois. Word was spreading of the favorable conditions in the Illinois Territory.

Many successful individuals have repeated failures before achieving ultimate success and William Morris was no exception. At age 39 with wife and four children, he uprooted his life to start anew 400 miles away. This time he was more discerning in selecting his new farm. After walking over his Illinois land, and also seeing the flat rock strewn Ohio farm, I discovered something intriguing.

I asked my son Adam, a certified geologist, to inspect Morris’s Illinois farmstead with me. Our aim was just to see what we could find with only a vague idea of seeing it through the eyes of an 1816 pioneer. While walking the adjacent Little Mary’s River creek bed, we discovered something astonishing.

This area is at the edge of a geologic structure known as the Illinois basin. Imagine a bowl shaped geologic structure encompassing most of Illinois. The edges of the bowl rise to the surface in Randolph County, Illinois as they do over near the Wabash River in Indiana. Why is this important? Because that is where you can find coal seams nearly at the surface. In the case of William’s Illinois land, you can literally see the coal seam in the riverbank. Below the coal seam is a layer of fire clay, and below that is Palestine sandstone. There is more.

In examining the early GLO maps another revelation appears. Morris’s original 160-acre farm in Illinois occupies an area of fertile prairie but borders an extensive woodland. It is shown on the map below as the southwest quarter of section 26.

This land was chosen with careful consideration. In one 160-acre plot, you have fertile prairie grassland, woods for lumber, a clear running creek, coal, fire clay and sandstone suitable for construction. William had learned much about how to choose a piece of land for pioneer settlement.

Ironically, the Ohio land he left behind is today valued at $7,000 per acre, a thousand more than the Illinois land. But for William, the ability to easily dig coal meant cash money to pay the mortgage, and a way to keep his log cabin warmer and brighter for his family. The fire clay would be excellent material to chink the log cabin exterior, and the sandstone would make a good foundation for the cabin. Morris was a consummate stone mason, quite evident by the stone work he left behind.

The Journey to Illinois

The question that has always nagged at me is, “What was the exact route?” We know that the first steamboat made its way down the Ohio to St. Louis in late 1816, so that mode of transportation can be ruled out for the Morris family. It was still quite experimental and dangerous. Earlier pioneers from Virginia to Ohio had used rafts but this was not practical for a move to Illinois since rafts don’t float upstream. Traveling with family and possessions most certainly meant a horse drawn wagon. There are accounts of emigrants on that trail using only a one horse, two wheeled cart for transport. Many had a team of horses pulling a covered wagon.

For William Morris traveling by wagon with his family, possessions and livestock, how difficult was the journey? Traveler David Thomas recorded the weather along that the likely trail as he moved west through southern Indiana in 1816.9 Tracking that 120-mile distance in 6 days meant progress of twenty miles per day by horseback, consistent with other accounts from the period. For the entire 400-mile journey, the best case scenario meant the Morris family was on the trail twenty days. A more realistic estimate is closer to a month.

With Betsy’s recent childbirth, she would not be able to ride, condemned to walking the entire 400 miles. That factor alone likely made the trip longer. She would still have to maintain a pace of at least nine miles per day, stretching out the trip to 45 days.

On the 7th of November I left Corydon, and arrived on the 13th. (at Vincennes) On our way, the snow fell about three inches deep. The weather from that time till the 20th was cold, when it became mild, and continued so till the 10th of January. On the morning of the 18th, the mercury stood eleven degrees below zero; the Wabash River closed, and has remained so ever since. [10th February 1817.] 10

This timeline charts out the “window for travel” in the fall of 1816.

September and October, William and 14 year old son Samuel collect the harvest and prepare for the move to Illinois.

Oct. 29th, 1816, Ephraim Morris, third child of William and Betsy Morris is born.

Nov. 10th - snow and cold weather.

Nov. 20th - Weather turns mild.

Nov. 27th - Four weeks after Ephraim’s birth, earliest date Betsy could have traveled.

January 10th - mild weather turns cold, winter arrives with force, 45 days after Nov. 27, 1816.

It is apparent that the 45-day (Nov. 27 - Jan. 10) window was enough for the Morris family to complete their journey. The major rivers to cross including the Wabash (divides the states of Indiana and Illinois) as well as the White River and East Fork White River. An eyewitness account from the summer of 1816 records fording both the East Fork and main fork of the White River with no difficulty. The Wabash would have to have been crossed with a ferry at Vincennes.11 Other travelers making this same 1816 journey noted frequent taverns and recounted that they only had to sleep outdoors a few nights during the entire trip.12

The advantage of traveling this time of year were several. Insects were not a discomfort, and this was no small thing in 1816. In addition, the dryer conditions made roads firmer and smaller streams easier to cross. The cooler temperatures were preferable to scorching hot weather. And most of all, William was able to harvest his crops before departure, regardless of how meager. But it was the backwards weather of 1816 that provided the best advantage of moderate temperatures and generally dry conditions.

How did William’s story end? He had success with his Illinois farm, in the end owning over 500 acres with his sons. But tragedy struck repeatedly. Betsy died during the great winter freeze of 1831, likely of lingering complications from the birth of her last daughter, Alice, six months earlier.13 In 1834, the first wave of cholera to Illinois killed William and Betsy’s two oldest children, Jane and Newton on the same day in July. Their bodies were buried in a single grave at Union Cemetery.14 And in 1844, not only did the great Mississippi flood of that year destroy Kaskaskia, but the resulting spread of disease was also responsible for the deaths of two grandchildren, four year old Mary Ann and infant George. The likely culprit was once again, cholera.

William turned his grief into art though I doubt he would have called it that. He carved at least thirty gravestones for departed family members and friends. Many were for grandchildren and in-laws that he helped place in the ground of Opossum Den Prairie. The exception was for his wife, Betsy. Her large and elaborate burial monument was obviously made by a professional carver. But even there, William seemed to have had a hand in the selection of an epitaph.15 The image below shows a typical marker carved by Morris, using Palestine sandstone and exhibiting his quaint style.

Why did William Morris move to Illinois in 1816? The 1816 farm harvest may not have been a total loss, but was likely enough of a loss with the balloon payments coming due to force his move. Like thousands of other emigrants that same year the answer lies in the magnet of cheap land as well as the urge to leave other troubles behind.

By 1818, Illinois boasted a population of 35,000 in official tallies (that were perhaps exaggerated). The population had almost tripled since 1810 when the population was about 12,000. Most of those people moved to Illinois after the conclusion of war in 1814. Perhaps about five thousand people per year moved to Illinois each year from 1815 through 1818. That means a dozen or more people were starting down the Illinois trail every day for four years. The Morris family was in good company on their journey.16

H. H. Lamb, Climate, History and the Modern World, 2nd ed., (London and New York, Routledge, 1995.

One important discovery in climate science is that colder periods are associated with extreme variation in temperature. So, very high temperatures are recorded during cold periods along with very cold temperatures. This is thought by archaeologists to be one of the reasons why agriculture developed suddenly ten thousand years ago, independently around the world. A warmer, but more importantly, predictable temperature was more conducive to agriculture.

Morris Birkbeck in “Letters from Illinois” calculates it cost half as much to set up a farm in the American Northwest Territory compared to an English farmer, considering all in costs such as seed, tools, land, animals, etc.

Ft. Brier (sometimes spelled Briar) was a fortified blockhouse whose purpose was to connect a supply line from Cincinnati up to Ft. Meigs. It was primarily a cattle station to supply beef to the troops farther north. The exact location had been lost to time and was only re-discovered several years ago. GPS coordinate 40°11'49.4"N 84°32'52.7"W

David Thomas, Travels through the Western Country in the Summer of 1816, (Auburn, New York, Printed by David Rumsey, 1819).

The War of 1812 concluded with the Treaty of Ghent. The U.S. Government had borrowed heavily to finance the war which in turn had created inflation in prices. The cessation of hostilities eased this burden on the economy.

Klingaman and Klingaman, The Year Without Sumer:1816, (New York, St. Martins Press, 2013) 105.

Klingaman and Klingaman, 1816, 152.

Thomas, Travels Through, 1819, 199.

Thomas, Travels Through, 1819.

Thomas, Travels Through, 1819.

Morris Birkbeck, Letters from Illinois: With Notes on a Journey in America, from the Coast of Virginia to the Territory of Illinois, 4th ed. (London: Taylor and Hessey, 1818).

Serengenity@Substack.com, Cause of Death, 2024.

Determined by Ground Penetrating Radar in 2024. Only Newton’s headstone remains. Jane’s headstone was reported in genealogical data previously but is today missing.

Serengenity@Substack.com, Shakespeare and Pope come to Opossum Den Prairie: a 400 year journey of words, 2024

There was such a large number of people from Preble County, Ohio that emigrated to Randolph County, Illinois that the local library in Sparta, Illinois maintains genealogy records for Preble County, Ohio. The two counties are connected by history and blood relations.

Fascinating story and so well researched. How amazing to have such well documented resources to help piece the story of William and his family.

I have ancestors that were impacted by the 1906 eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in Italy. The ensuing drought and disease led to the eventual decision to leave Italy and give up on the unpredictable life of a farmer.

Prior to steamboats, I think a lot of the time people would use a flatboat pulled by an animal on the riverbank to more easily transport stuff down the rivers. May have been an option for your folks. :-) Very cool how you have connected a volcanic eruption far away to your ancestors' stories. On another note, I seem to find a lot of connections to Abbeville, South Carolina, in my own research and have long wondered if there's any connection to the town with the same name in Abbeville, Louisiana, haha.