Finding John & Jane Beaty

Mid 19th century marble marker broken, buried, moved and set in concrete. Their Gr Gr Gr Gr Granddaughter put it back together.

A friend asked me to help her with some damaged family grave markers. They were in bad shape and appear to have moved. Moved? Grave stones don’t normally just get up and move. Oh, this is gonna be good!

Kathleen was puzzled that the markers were not where she remembered them. She consulted her sketch map made several years before on her last visit and sure enough, they seem to have moved. And also, they had been “repaired.”

You don’t move a marker from one grave and put it on someone else’s. You just don’t.

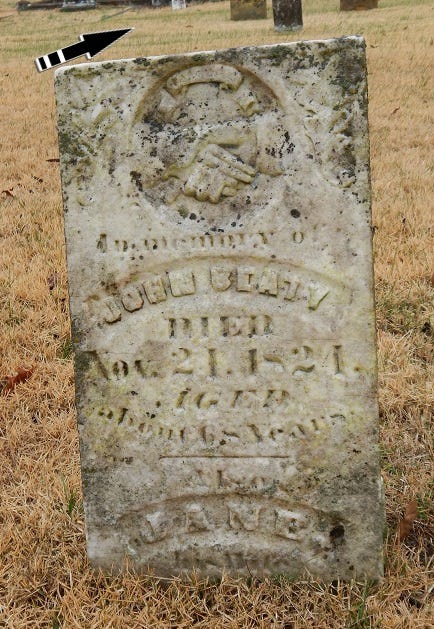

We found the marker for John & Jane Beaty (Bate’ ee) (b. 1758 / 1765 d. 1824 / 1835) which was broken and plopped into wet concrete only six inches in front of an unrelated marker, obviously the wrong place. At this point we were missing the bottom portion of the marker, the base stone and lacked certainty of its proper location. We then began the work to determine what happened and to mitigate the damage.

First we needed to confirm that it was in the wrong place and then locate the original location. But how can we do that? There are about 800 burials here with many downed markers and we had no idea where to look. I examined the FindAGrave1 information to see if there were clues of some sort. We studied the genealogical relationships, and speculated that the correct placement might be next to some of his relatives. And then I got an idea.

A Clue!

The FindAGrave memorial page had a 2015 photo taken by John Meachum, a retired newspaper reporter. I contacted Mr. Meachum by email, explaining our dilemma. He wished us luck and granted permission to use his photo but could not add any material facts. I downloaded and enlarged the photo and studied it in magnified detail. And then I saw it! Barely visible at the top of the photo was the tiny image of two sandstone markers with a marble marker in front. And on the far left was a stone or concrete rail. If Meachum had tilted his camera just a few degrees lower, we would have had no clue. Maybe this will help us to fix an exact location!

Using the FindAGrave app on my phone, I pulled up the photo and walked around the cemetery holding the phone in front of me to align the photo with my surroundings. I had never triangulated a buried stone before like this but it worked surprisingly well. After walking around, backwards, forwards, side to side I felt I finally had the position. And literally my foot was on a worn stone in the turf that could be the missing base and bottom portion of the John Beaty marker. Could we be that lucky? Only excavation will tell us with certainty.

We found it! The marker is broken in four pieces total. Two are in the above photo (the piece stuck in the slot, and the piece immediately above the rectangular base). The piece of stone at top appears to be part of an unrelated footstone discarded in the past. The other two pieces are the original top found in concrete and one other section we discovered just lying against another nearby monument. We now have all the pieces and best of all, the limestone base is in good shape and usable.

And now for the really really hard part.

There was still the concrete that encased the top section of the Beaty marker. And it has to come off. This is the most difficult and risky task in historic grave marker conservation and some conservators would not even attempt it. To do properly is both physically exhausting and time consuming. And one wrong move can damage the marker further. I decided to try. I have done this twice before; the first time was a failure and the 2nd time, successful. How will the third time go?

I positioned the concrete encased marble marker on a wooden platform outside on the driveway. This process is very messy. Water and concrete chips fly everywhere! I tarped off my truck to protect it, laid out the tools and got the garden hose ready. Water is essential as it soaks in and weakens the concrete a bit, but it is especially helpful to contain dust and cool the diamond tip saw blade. Here we go!

Disclaimer: This is a very difficult procedure (more complicated than this video makes it look) and should not be attempted without substantial experience in historic grave stone conservation. Using a sanding block and muriatic acid (diluted) is not recommended and was used in this case only as a last resort. To control the reaction I used the acid in controlled 10 or 15 second bursts after which the acid was neutralized with water and generous quantities of baking soda. Diluted muriatic acid is about pH 2 and can severely react with marble made of higher pH calcium carbonate (CaCO3).

With the concrete removed, we then began reassembly of the marker. Here we see (below) the trial fit of the pieces. I made the decision to chisel out the remaining eroded portion in the base slot and trim off the bottom portion of the bottom section shown in the photo below. This reduces the height of the marker by two inches but gives us better integrity. We were then able to reassemble the marker from the bottom up. The lower section will be carefully leveled and mortared into the limestone base with 3.5 NHL limestone mortar.2 Succeeding sections will be reattached using Litho-Glue,3 an adhesive mortar and clamped into alignment.

About John and Jane.

We know little about the life of John Beaty. He was born in County Down, Ireland in 1756 and died in Randolph County, Illinois in 1824 as his gravestone attests. He first immigrated to Abbeville, S. Carolina where he married his wife, Jane Cochran before they came to Randolph County, Illinois with their children in 1808.

John was described in the 1883 History of Randolph, Monroe and Perry County4 as

…a retired and quiet man, yet esteemed a valuable citizen, and a man of considerable force of character ; he left three sons, some of whom are living.

We know that his daughter Hannah, loved him enough to spend money on a marble grave marker. And that is something because many from that period were buried in an anonymous grave somewhere on their pioneer farm; only a fieldstone for a marker at best.

It was common during this time for graves to be marked with simple wooden crosses or fieldstones. And then local sandstone was used for a time. But sometime around 1850 that changed in Southern Illinois. Transportation systems improved but so also did the industrialization of Midwestern cities like St. Louis and Cincinnati. Affordable professional grave markers were now available.

Hannah died in 1877 and the style of marker was generally not available prior to 1850, so it seems Hannah put up a replacement marker for her parents sometime between 1850 and 1877. Her unmarried brother Charles died in 1864 so maybe it was at that time Hannah decided to also place a new marble marker for her mother and father. Whatever the details, Hannah clearly wanted her mother and father to be remembered. And so we do.

FindAGrave.com is a free website that allows the public to search and add to an online database of burial sites and is owned by Ancestry.com

This is a mixture of fine sand and Non Hydraulic Lime mixed together (2.5 parts sand to 1 part lime). The 3.5 designation indicates the hardness of the cured mortar. It comes in grades of 2, 3.5 and 5, with 5 being the hardest set.

Litho-Glue is a proprietary product of Limeworks.US, composed of an NHL mortar with casein glue. It is superior to epoxy adhesives because of its ability to allow moisture to move through the stone unimpeded, thus resolving the “rising damp” problem in stone repair.

McDonough, J. L. & Co., Combined history of Randolph, Monroe and Perry counties, Illinois . With illustrations descriptive of their scenery and biographical sketches of some of their prominent men and pioneers., Philadelphia, 1883.

Incredible work! Kudos!