Her death was a mystery to me. Betsy had died at age thirty-seven after bearing ten children, the youngest of which was my Great great grandmother. It took decades to finally discover the cause of her death, and even then with only a probabilistic certainty.

Her grave stone is impressive for the year 1831, and marks the very first burial in Union Cemetery. The size and weight of the stone marker is substantial and reflects the great loss to her family. Her husband, William Morris, was left with ten children ages seventeen through six months at age 53. He never remarried.

In Illinois, death records do not generally exist before about 1916 when statewide death certificates became mandatory. Randolph County records show cause of death in family genealogies, oral histories, county histories, church records, and of course the 1850 and 1870 mortality census records. And there is the one off discovery of medical records in estate files. But generally, one is left with circumstantial evidence for cause of death.

The first clue to Betsy’s demise was the date of death itself, January 15th, 1831. The book, Frontier Illinois, by James E. Davis remains possibly the most complete history of early Illinois and contains on page 244 reference to “the lethal legendary Deep Snow of 1830-1831.”

Following downpours, deep, unrelenting snow blanketed Illinois, killing humans and animals and etching itself in personal and collective memories. Some persons simply vanished, while others’ remains were found with spring’s melt. Lingering cold hurt corn, game was scarce for years, and cotton fields in southern Illinois perished, never rebounding. Some Brown County residents gave up and fled. Stalwart residents of Pike County stuck it out, despite dangerously depleted liquor supplies. Indians slew immobilized animals, amassing extraordinary meat supplies, Spring melt water turned creeks into impassable torrents, restricting movement. From 1832 into 1834, cholera swept some survivors to their graves.

To get some sense of the carnage, I used the Find A Grave website to survey the dead in Randolph County for the year 1831 expecting to find a significant increase in burials for 1831. Only three surviving gravestones mark burials in the county for the entire year of 1831. By contrast the two previous years had two and four marked burials respectively, so 1831 was in line with the previous years. There was no spike in deaths it appears and the deadly affects of the blizzard appeared exaggerated. People were inconvenienced shut ins, but did not appear to die in large numbers. The following year of 1832 listed eight marked burials including that of 27 year old Dr. Meek, no doubt a martyred victim of the cholera plague that hit Randolph County that year.

And that is about where I hit a dead end. I thought I would never know what happened to poor Betsy. Cholera tends to hit in the warm summer and early fall months and it didn’t really strike Randolph County until about 18 months after Betsy’s death, so that was a very unlikely cause. And none of the other family members died that year, so even a different communicable disease seemed remote. Impasse.

On a whim one day, I was playing around with Artificial Intelligence or A.I. as it is known. I had already explored Co-Pilot, Grok and Gemini and found them moderately useful in creating artistic renderings of ideas. But what would they say about Betsy? I typed in a full description of Betsy including her age, date of death, weather, number and spacing of children, her background; basically everything I could think of that might be remotely relevant to her death. And after about ten seconds of “thinking” Microsoft Co-Pilot gave me the answer.

Betsy had died of a hemorrhage or infection related to lingering problems from her recent childbirth six months earlier on June 6, 1830. It all fit. The scenario then became one of a medical crisis and because of the immobilizing snow, there was no way to get treatment from a doctor, as inadequate as it might have been. Imagine her family, watching Betsy dying, no way to get a doctor, and cooped up in a log cabin (or small house by then).

It is painful to think what happened next. Where did William store his dead wife’s body? It would be impossible to dig a grave for many months, so one can only imagine, wrapping the body in its burial shroud and placing it in a wooden box, storing it where; in the barn or some out building protected from predators and the elements? I suddenly find myself not wishing for “the good old days.”

Encouraged by my success at finally figuring out what happened to Betsy, I began to think of other deaths and their cause. I have omitted many of my “false starts” and “rabbit holes” in the interest of brevity. Here is a summary of deaths sorted by age group for Randolph County, Illinois sourced from the special 1850 Mortality Census.1

Numbers represent the percentage of each age group that died from a listed cause. Note that age group 6 through 10 only had 5 individuals so is perhaps not reliable data. The other groups had decent sample sizes of 49, 16, 44 and 32 individuals, respectively. In total 146 deaths were recorded. Only two were accidents; a horse kicked a child to death and drowning of an adult male. There were no murders. I merged some categories such as Encephalitis and Meningitis in order to make the data more usable. The unknown category includes “chronic unknown,” unidentified “fever,” as well as just “unknown.” Some categories were broad like “Congestive Fever” which may include heat disease but more likely mosquito born Typhoid or Malaria. Some diseases were easily identified such as consumption and cholera. The disease conditions of hives, worms and cholic are suspicious probably indicating the child died from something else while also having the stated condition. It is interesting that the age 11-20 age group had a significantly higher death rate from Congestive Fever, Erysipelas, and Typhus, all indicative of insect transmitted disease, suggesting outdoor farm work in those teenage years.

It is not surprising that of the prime adult years of 21 through 40, childbirth was listed as the killer of 11% of all adults. Adjusting for sex, that means about 22 percent of women’s deaths were from childbirth related complications. In a non cholera year, the prime adult female deaths from childbirth would be about half. The 1850 census also includes “length of time of disease” which in the case of childbirth deaths is often one to two weeks, the length of time a serious infection would take hold and kill the woman. Country doctors and midwives were not big on hand washing it seems.

Even though the deaths recorded were from June 1st 1849 through June 1st 1850, early in the second major cholera epidemic, cholera was already evident as a major cause of death approaching half of all deaths. The significant percentage of dysentery deaths were likely caused by a parasite infection of the G. I. tract related to contaminated water as was cholera. Cholera was easily diagnosed because it was the only disease associated with uncontrollable diarrhea that killed its victim within 48 hours. On the original 1850 census documents, there is a hand written notation that most of the cholera deaths were in the river town of Chester and that within Chester, the deaths concentrated in the lower part of town near the Mississippi River. Now, this is interesting that cholera was sweeping through Chester in the 1849-1850 period since the Sparta area, ten miles to the east did not see a significant number of cholera deaths until 1852, indicative perhaps of the spread from the initial contamination outward from the river.

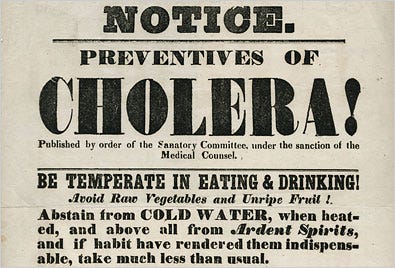

Cholera

became endemic after its arrival to Illinois in 1832 and remained the king of epidemics throughout the nineteenth century. In the Possum Den area of Randolph County, the big Cholera years were 1832-1834, 1850 - 1854 with spikes in 1852 and 1854. At Union Cemetery there are 50% more deaths recorded in those two years. The cause of the disease was not generally understood by the populace until after the Civil War. Often, the culprit was drinking contaminated water from a well situated close to an outhouse.2 Raw sewage flowing into nearby rivers was also a common source of contagion. Once sanitation improved, the disease faded to obscurity. The great sadness of Cholera was its tendency to strike quickly and kill multiple people within the same family. The symptoms are horrendous; namely an unholy pallor on the face accompanied by diarrhea so bad, the epithelial cells of the intestines are expelled. And thinking the disease was spread by “miasma,” family members would remove the bedding and personal items of the deceased to a pile outside to set it ablaze. A sadly predictable footnote is the tendency for city fathers to downplay the disease, lest it chase business away from their mercantile interests.

Tuberculosis

was a significant killer of young adults and remained endemic throughout most of the nineteenth century. Because it is mildly contagious and somewhat genetically based, it can run in families. One family buried at Union Cemetery lost a number of children in their twenties. Of the nine adult children of David and Polly Hawthorne, the oldest four, born before 1818, lived in age from 45 to 70. The youngest five children born in 1818 and later when the family relocated from S. Carolina to Illinois via Ohio and Tennessee lived to ages, 21, 26, 28, 22 and 22, all in the 1840s. This is highly suspicious of picking up T.B. on their travels and then spreading it to the remaining siblings.

Church records reflect that Alexander Campbell also died of consumption at age 22 (April 24, 1867). Alexander’s mother is Sarah Hawthorn Campbell, one of the Hawthorn siblings noted above that likely died of T. B. as well. Did Sarah pass the genetic propensity for T. B. to her son, Alexander? Or was it merely the close contacts of family members that spread the disease? Both the Hawthorn and Campbell residences were in close proximity, southeast of the village of Blair, Randolph County, Illinois. Medical research is divided on how exactly T. B. develops in the body and how long the incubation period is. Ostensibly the disease develops within a few months to a few years. But it seems suspicious here that it appears to run in the family.

A confounding narrative is that one of the siblings is listed in the 1850 mortality index as dying from Typhus. Typhus is a bacterial infection spread by insects such as chiggers, lice and fleas. Since four of the five deaths were during cold weather months, it seems unlikely that chiggers and fleas played a role. It is likely four of the five died of consumption and William was the outlier, dying of typhus or perhaps dying of consumption while having typhus, producing a confused diagnosis. Regardless, this is indicative of very poor and unsanitary living conditions and was a frequent killer of young adults. Doc Holliday, perhaps the most famous person of that era to die of consumption, died at age 36 in 1887 six years after the legendary shootout at the OK Corral.

Yellow Fever

is considered to be a southern malady, spread by mosquitos in the warm swampy waters of the south. The disease was so notoriously bad in New Orleans that young women would not marry a man who had not been there long enough to “acclimate” to the fever but the disease was sporadic in Illinois. Yet, in 1878, it spread up the Mississippi River valley to do significant harm to St. Louisans and certainly impacted Randolph County in southern Illinois with it’s many rivers such as Mary’s, Plum Creek and the Kaskaskia. The significance of this is that disease records generally record the extremes and are inexact in describing the extent and detail of epidemics.

Milk sickness

is perhaps the only disease confined geographically to southern Illinois, and the Ohio River valley in general. It is caused by drinking milk from cows that have eaten the very poisonous White Snakeroot plant. But by 1830, Anna Hobbs Bixby had discovered the cause by listening to the advice of an old Shawnee woman. Once farmers eradicated the white snakeroot and controlled the grazing of their cows, the problem disappeared and is virtually unheard of today.

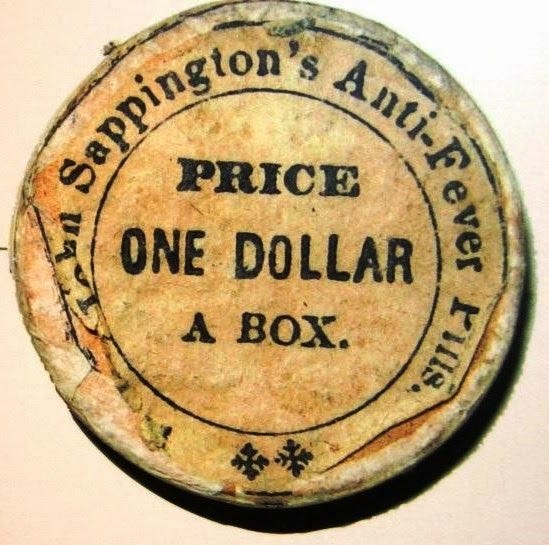

Malaria

is perhaps one of the medical success stories of the American frontier. Ague /ā′gyoo͞/ as the disease was known then, is caused by a single celled parasite that spreads through mosquito bites. The Old Northwest Territory, rife with rivers, creeks and mosquitos was prime malaria country and remained a common and recurring affliction although not often fatal. Dr. John Sappington of Arrow Rock, Missouri developed quinine as a curative for malaria and marketed it aggressively from 1832 to 1844, amassing a fortune in the process. Dr. Sappington’s Anti Fever pills were very popular and later used as a preventative as well as a curative for malaria and generalized treatment for other fevers. In 1844 he published the first medical book west of the Mississippi River called Theory and Treatment of Fevers and in so doing gave away his trade secret to the world.

Scarlatina

is an associated advanced stage of viral Scarlet Fever resulting in death about 20-35 percent of the time in pre anti-biotics nineteenth century. It often strikes school age children between five to ten years old although in 1850 Randolph County most of the deaths were age five and under.

Measles

is a highly contagious virus usually striking those children under five years of age and resulting in fatality rate varying from 5 to 30%. The disease course often results in pneumonia or encephalitis. Vitamin A deficiency is highly linked to the severity of the disease, so the administering of Vitamin A rich foods such as beef liver or Cod liver oil is quite beneficial to young children. There were no reported deaths from measles in the 1850 Randolph County mortality census. It is possible that 1850 was not an epidemic year for measles, understating its occurrence.

Influenza

deaths were common, especially for those under age one and over age 65 or with co-morbidities. Similar in function to pneumonia, it often is the final disease that kills off the weak and sick. Many diseases were endemic and always seemed to be in the background. The interplay of disease is also notable. Imagine surviving Ague (malaria) and summer Cholera, but in a weakened state with the arrival of winter, pneumonia delivers the final blow. So, what was the cause of death then?

This link below shows the 1856 disease map of the world which includes the general areas of many prevalent diseases.

For the historian or genealogist that seeks to identify the cause of death for their own subjects, here are some avenues to explore:

County histories are great sources of anecdotal information. Deaths are often recorded especially if the person is notable or the death is especially tragic.

If you are lucky enough to have an ancestor die during June 1st 1849 through May 31st 1850, they may be listed in the 1850 Mortality Census. Similar mortality records were recorded in subsequent census years. At the very least, the census will give you a representative cause of death for your area.

Genealogies often record deaths, sometimes partial information is given as to the place or general circumstances.

Creating a timeline of local epidemics, recessions, major immigrations, economic disasters and the like can be useful in understanding context.

County death records in some cases may predate official death certificates.

Find A Grave website has a searchable data base that can be used in a number of ways. One is to find all deaths (with surviving grave stones) within a single year in a single community, county or state. Some gravestones may even state the cause of death.

Sibling deaths can be especially relevant. For example two of Betsy’s children died on the very same day. One is recorded as Cholera and knowing that Cholera usually kills 20 percent of family members when it strikes it is nearly a certainty that the other sibling also died of Cholera.

With the passage of time, A.I. will become more useful in this research. We are only at the beginning stage but already there is great promise with this new tool.

Ancestry.com. U.S., Federal Census Mortality Schedules, 1850-1885 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. A portion of this collection was indexed by Ancestry World Archives Project contributors. Original source, Census Schedules for Illinois, 1850-1880. T1133, rolls 58-64. National Archives and Records Administration, Washington D.C.

Daly, Walter. (2008). The Black Cholera Comes to the Central Valley of America in the 19 Century - 1832, 1849, and Later. Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association. 119. 143-52; discussion 152.

A very interesting article. It is a sad fact that so many women died in childbirth or soon after. Infection caused by not washing hands was often the cause of postpartum deaths. I used to write a history blog and wrote about cholera in London, and how Dr John Snow was instrumental in finding the cause of an outbreak https://motleytalk.substack.com/p/motley-talk-about-john

Fascinating article. So many interesting facts about disease. I love the way you put everything together from symptoms to family members to migration to length of disease time to age of deceased to geography to the weather. And still write about it in an interesting way.

What is congestive fever? What would be congested? Is it the way we think of congestion today, like of the lungs or upper respiratory? I am thinking of my great-grandmother's child who died age 2 of congestion of the brain.

When I saw hives, I thought of an allergic reaction, maybe to a bee sting.